You can feel fine in your seat, then stand up to speak and your throat suddenly feels smaller. It doesn’t have one single setting. People report it in a conference room at Google, at a wedding toast in London, or during a class presentation in a U.S. high school. The core mechanism is that the body treats being watched as a possible threat. That flips on the stress response. Breathing, muscle tone, and saliva change within seconds. The throat is where those systems overlap, so it’s a common place to notice the shift.

Being watched changes your nervous system fast

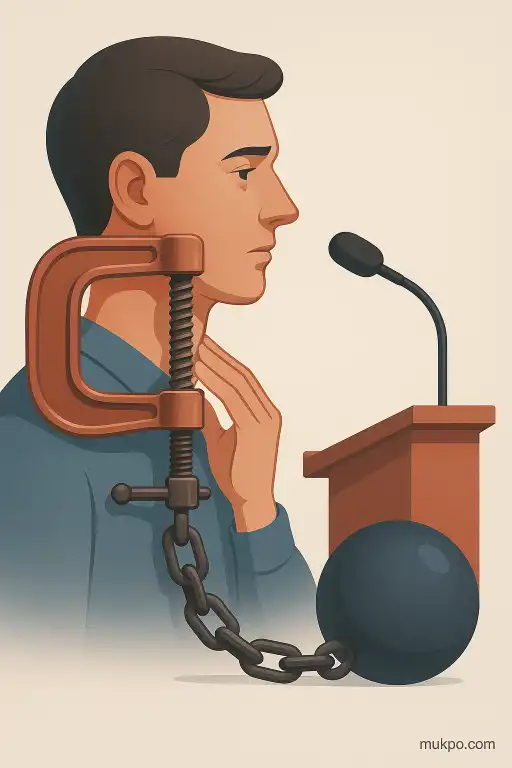

Public speaking has a social risk baked into it. You’re being evaluated, and you can’t fully predict how people will react. The brain areas that scan for danger don’t separate “lion” from “group disapproval” very cleanly. When the sympathetic nervous system ramps up, it primes the body for action. That includes tightening certain muscles and shifting blood flow toward big muscle groups, not fine control.

The throat sits at the crossroads of breathing and swallowing, and both are strongly linked to threat detection. One overlooked detail is that swallowing is partly a “safe moment” behavior. Under stress, the timing and frequency of swallows can change, and the sensation can feel like constriction even when the airway is open. People often interpret that as “my throat is closing,” even though it’s usually a coordination issue, not an actual blockage.

Dry mouth isn’t just uncomfortable, it changes the feel of speaking

Stress commonly reduces watery saliva. That’s partly due to sympathetic activation and partly due to breathing patterns. Less lubrication makes the back of the throat feel scratchy or tight, and it makes each swallow more noticeable. It can also make consonants feel harder to form, because the tongue and lips depend on a slick surface to move cleanly.

There’s also a small mechanical effect people miss. Saliva normally helps the vocal folds vibrate smoothly. When the surface is drier, vibration can feel effortful. A person may start pushing with the neck muscles to compensate. That extra effort gets read as “tight throat,” even though the real change began with moisture and friction.

Breathing shifts, and the throat notices first

A common pattern before speaking is a quick inhale that’s a little too high in the chest. It happens when someone stands, turns toward the room, and tries to start on the next breath. That kind of inhale uses accessory muscles in the neck and upper ribs more than the diaphragm. Those same neck muscles attach around the larynx area, so the inhale can come with a subtle lift and squeeze sensation.

Carbon dioxide levels can also change if breathing gets shallow or fast. Even a modest shift can heighten bodily sensations and make the throat feel “off.” People often think they’re not getting enough air, but the feeling can come from breathing patterns that disrupt the normal balance of gases, not from a lack of oxygen.

Your voice box is small, sensitive, and easy to over-control

The larynx is built for tiny, rapid adjustments. Under pressure, people tend to monitor themselves more. That monitoring often turns into extra muscular control. The muscles that raise the larynx and narrow the space above it can engage more than usual, especially right before the first words. The result is a squeezed sensation that may peak at the exact moment the person tries to start speaking.

A situational example is the “first sentence problem.” Someone can chat normally before a meeting, then feel tightness when they say, “So, today I’m going to…” The shift isn’t mysterious. The body moves from casual turn-taking to sustained projection, and that invites more tension in the structures that stabilize pitch and volume. The throat feels it because that’s where the stabilizers live.

Attention and memory can make the sensation louder

Once a person has noticed throat tightness in public once or twice, the brain starts checking for it. That checking increases attention to sensations that would normally stay in the background. The throat has dense sensory feedback, so it becomes an easy target for that spotlight. The sensation can feel stronger simply because it’s being tracked moment by moment.

Past experiences matter too, but not always in a neat way. For some people it’s linked to a specific incident, like freezing during a university presentation. For others it’s vaguer and seems to appear only with certain audiences, like senior leadership versus close teammates. The common thread is that social evaluation raises arousal, and arousal makes the throat’s small changes feel big.