A museum display that asked for belief

It’s easy to forget how much a museum label used to do. In 1842, visitors at P. T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York City were shown something billed as a mermaid, and a lot of people leaned in instead of laughing. The trick wasn’t just the object in the case. It was the whole situation around it: the posters, the story, the “expert” descriptions, the suggestion that respectable people had already been convinced. You didn’t have to be gullible to feel the pressure of that room. You only had to be curious, and slightly unsure of your own judgment.

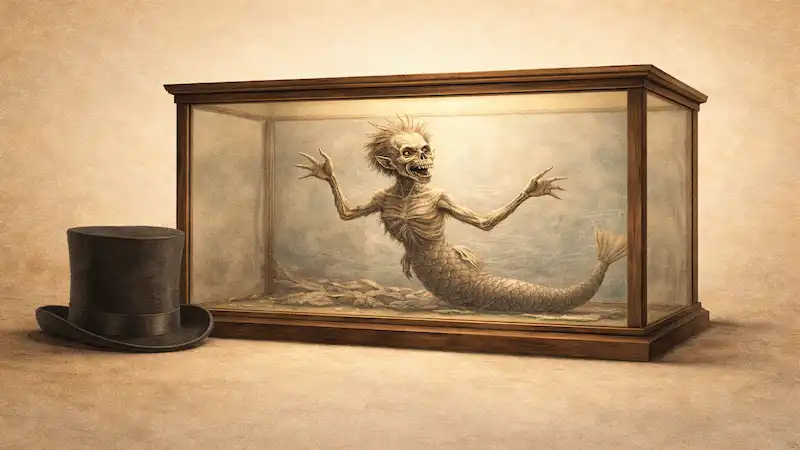

What the “mermaid” actually was

The famous specimen was the “Fiji Mermaid,” and it wasn’t a smooth, romantic creature. It was a small, dried figure that looked more like a grim little mummy: the upper body resembled a monkey, the lower body a fish. These kinds of objects were often made in the 18th and 19th centuries by stitching or wiring parts together and then drying and varnishing the result. Barnum did not invent the object itself, and the early chain of ownership gets fuzzy in retellings, but he became the best promoter it ever had.

A detail people overlook is the scale. Many imagine a life-sized siren. The Fiji Mermaid was compact, which mattered. Small things can be displayed like precious evidence. They also hide seams and joins better under glass, in low light, with a crowd jostling behind you.

The sales pitch was a machine, not a sentence

Barnum’s method worked because it didn’t ask the audience to make one big leap. It offered lots of smaller steps that felt reasonable. A newspaper item. A printed handbill. A lecture. A confident attendant who had an answer ready. The mermaid could be framed as a scientific curiosity one moment and a moral wonder the next, depending on who was listening. That flexibility mattered in a Victorian public that treated “natural history” as both education and entertainment.

He also understood that argument is not the same as attention. People came partly to test themselves. Could they spot the trick? Could they defend their disbelief? A hoax that invites debate keeps selling tickets because each side needs an audience.

Why ministers and “respectable” visitors got pulled in

It sounds strange now that clergy could be among the persuaded, but it fits the moment. Natural theology—the idea that nature’s oddities could be read as evidence of design—was still a familiar way to think. A “mermaid” did not have to feel like a pagan fantasy. It could be treated as an exotic creature from a distant ocean, or as a puzzle that proved how wide creation really was. In that setting, disbelief could look like cynicism, and belief could look like open-mindedness.

There was also social risk in being the only person sneering. A museum crowd creates its own authority. When others are staring seriously, reading the placard, asking questions, it becomes easier to suspend judgment. People often confuse the presence of institutional trappings—glass case, printed text, scheduled talk—with the presence of verification.

The reveal never killed the appetite for it

Plenty of viewers did call it out as a fabrication, and skepticism was part of the story almost from the start. But the mermaid’s power didn’t depend on lasting belief. It depended on the experience of seeing it “in person,” in a place that claimed to sort truth from nonsense. Even when people suspected a stitch-up, they still wanted to inspect it close, compare notes, and decide which details looked wrong. A hoax object becomes a kind of hands-on argument.

That’s why versions of these “mermaids” kept traveling through exhibits and collections long after the original wave of publicity. The creature in the case offered two shows at once: a monster story for the believers, and a craftsmanship puzzle for the doubters. Either way, the line at the display could keep moving.