It’s easy to think of fog as just weather, because it usually lifts. In early January 1952, London got something else. A cold spell pushed people to burn more coal, and a still layer of air trapped the smoke close to the ground. Over a few days the city’s normal damp haze thickened into a dirty, yellow-brown smog that sat in the streets. It was dense enough to stop buses, disrupt work at places like Smithfield Market, and even force the House of Commons to suspend sittings because members could not see to conduct business properly. The mechanism was simple: too much combustion, not enough wind, and a lid of temperature inversion holding it all down.

How the air got trapped

London had lived with coal smoke for generations, so the key change wasn’t just “more pollution.” It was the weather pattern. A temperature inversion formed when colder air settled near the ground while warmer air sat above it. That setup blocks mixing. Smoke from domestic fires, factories, and power stations stayed low and built up hour by hour.

The overlooked detail is how ordinary the sources were. A lot came from home fireplaces and small boilers, not a single dramatic industrial stack. When everyone heats at once, a city becomes a giant, distributed chimney. Add the natural moisture of London air and the soot particles gave water droplets surfaces to cling to, thickening the murk.

What “blind” looked like on the street

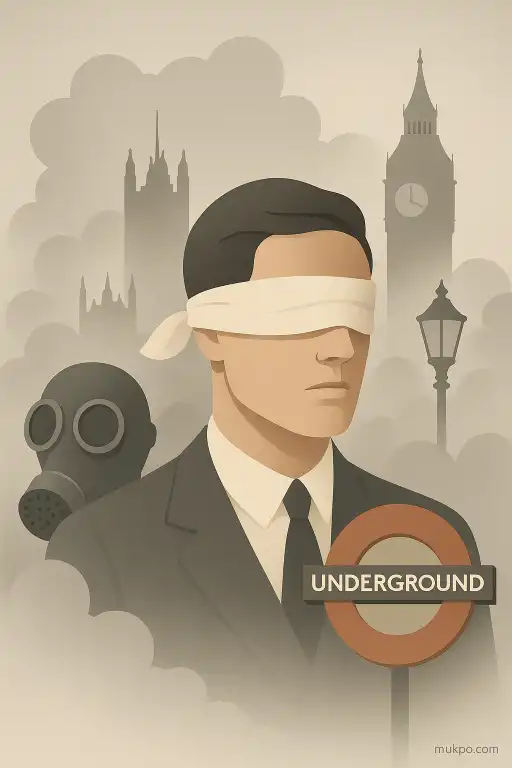

People described visibility dropping to a few feet in places. Drivers pulled over. Bus services were curtailed. Some trains kept running but at reduced speed. In parts of central London, pedestrians felt their way along walls and railings because familiar street layouts disappeared. The smog didn’t stay politely outdoors either. It seeped inside buildings, so cinemas and theatres reported haze in the auditorium and, in some cases, cancelled because audiences and staff could not see well enough.

One situational example that captures the day-to-day disruption is the way markets and deliveries struggled. Smithfield Market relied on early-morning movement of meat and produce. When vehicles and people can’t navigate, food distribution starts to wobble quickly. It wasn’t a dramatic “collapse.” It was lots of small failures at once, multiplied across a city.

Why it made people sick so fast

The smog was a mix of soot and sulfur compounds from coal, suspended in wet air. That combination matters. Sulfur dioxide can irritate airways on its own, but in a damp, stagnant environment it can turn into acidic aerosols that penetrate deep into the lungs. The result wasn’t just coughing. It was a wave of bronchitis, pneumonia, and respiratory failure, especially among older people, infants, and those already ill.

Deaths rose sharply during and after the event. The exact totals vary depending on how later analysts counted “excess deaths” in the following weeks. What is clear is that hospitals and general practitioners saw a surge that didn’t match a normal winter. Another easily missed point: many victims were not outdoors for long periods. Indoor exposure still happened because smoke-laden air infiltrated homes and public buildings, and coal fires burned inside as people tried to stay warm.

Stopping Parliament wasn’t the main disruption

It’s striking that the House of Commons had to suspend sittings, but Parliament wasn’t the centre of the practical damage. The larger disruption was the way the smog interfered with the invisible systems that keep a city running. When ambulances move slowly or get lost, response times stretch. When buses stop, workers can’t reach hospitals, power stations, warehouses, and depots. When visibility collapses, even routine decisions—crossing a road, finding a door—take longer and add risk.

The social impact also had a particular shape. Londoners were used to “pea-soupers,” so there was a tendency at first to treat it as nuisance fog. That normalisation mattered. If something is familiar, the early signals of danger get interpreted as inconvenience. By the time the scale of illness was obvious, the smog had already done its worst.

How it reshaped rules, fuels, and the idea of city air

The January 1952 event forced a change in what counted as acceptable urban life. It helped accelerate the political will behind cleaner air policy, most famously the UK Clean Air Act 1956, which encouraged smokeless zones and shifts away from raw coal in dense areas. The shift was not instant, and it wasn’t only about one law. It involved fuel supply, housing design, enforcement capacity, and the slow replacement of old heating habits.

It also changed what people expected from government and industry. Before, smoke was often treated as the cost of warmth and work. After, it became easier to talk about air as shared infrastructure, like water. That reframing is part of why this episode still gets cited when modern cities face pollution emergencies, even when the sources today are different, like vehicle exhaust or secondary particulates rather than coal fires.