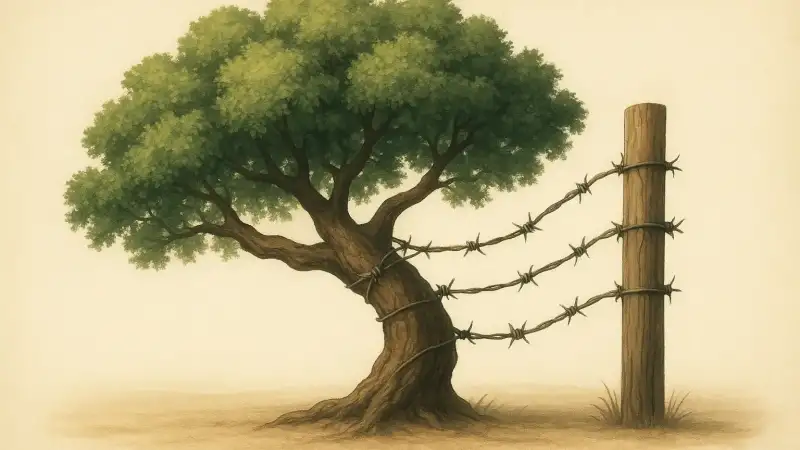

A tree in a place built to stop movement

People tend to think military crises start with missiles or troop movements. Sometimes they start with yard work. In August 1976, a poplar tree in the Korean Demilitarized Zone near Panmunjom became the trigger for a confrontation between United Nations Command forces and North Korean soldiers. The tree sat by a spot used for routine work and movement inside the Joint Security Area, where opposing sides stood face to face every day. Trimming it was supposed to be a minor maintenance job. Instead, it turned into a deadly clash and then an engineered show of force that made the world briefly hold its breath.

Why that tree mattered in the Joint Security Area

The Joint Security Area (JSA) is not like the rest of the DMZ. It’s small, tightly managed, and built around direct contact. That means tiny changes—where a jeep is parked, who carries what, which path is visible—can feel like a statement. The poplar tree was reportedly blocking lines of sight between UNC checkpoints. That sounds like a technical complaint, but in a place where observation is safety, visibility becomes power. If a guard can’t see a route, every routine movement starts to feel like an ambush risk.

There’s also the daily friction of “normal” work in an abnormal place. A work party with axes is not a combat patrol, but it looks like one from a distance. Even the act of stepping off a path can be read as a boundary test. The overlooked detail here is that maintenance itself becomes a form of communication. Painting a line, building a barrier, or trimming a tree can change how both sides move and watch each other the next day.

The clash during the attempted trimming

When UNC personnel went out to trim the tree, North Korean soldiers confronted them. Accounts describe an argument that escalated fast. In the violence that followed, two U.S. Army officers—Captain Arthur Bonifas and First Lieutenant Mark Barrett—were killed. The fact that they died during what was framed as a work detail is part of what made the incident so shocking. It wasn’t a firefight in a remote valley. It was close-range violence in the most watched square of ground on the peninsula.

Incidents in the JSA had happened before, but this one landed differently because it seemed to show that even “controlled” contact could snap. The mechanisms that usually keep things contained—procedures, observation, predictable routines—did not prevent a lethal outcome. After that, everything became about preventing a second surprise. Not preventing hostility, exactly. Preventing the kind that arrives disguised as a minor dispute over a tree.

Operation Paul Bunyan and the point of a spectacle

The response was not another small work party. It was Operation Paul Bunyan, a massive, highly visible effort to cut the tree down under heavy protection. The logic was simple and harsh: the next attempt would be overwhelming, controlled, and impossible to interrupt without escalating into something much bigger. The cutting itself became secondary. The real act was assembling a force large enough that the opponent would have to choose between watching or starting a war.

This is where “military spectacle” is not a media phrase but a tool. A spectacle sends information quickly, without negotiation. It tells the other side what you can deploy, how fast, and how far you’re willing to go to defend a seemingly trivial action. It also reassures your own personnel, who have to keep working inside the JSA the next morning. The overlooked detail is that a show like this is staged for two audiences at once, and those audiences want opposite things: one wants calm, the other wants deterrence.

How a small physical object becomes a political tripwire

It’s easy to ask why anyone cared about a tree. The better question is why a tree could carry so much meaning in that setting. In places like the JSA, objects become anchors for rules, pride, and risk calculations. A tree can mark a sightline, a route, or a habit. Changing it changes the “map” people carry in their heads. And when both sides constantly watch for tests of resolve, a practical act can look like a deliberate push.

After the spectacle, the tree was gone, but the conditions that created the crisis remained: constant proximity, symbolic boundaries, and the need to interpret the other side’s intent with imperfect information. That’s why the incident still gets remembered. Not because the object was important, but because the setting made it impossible for anything to be merely practical for long.