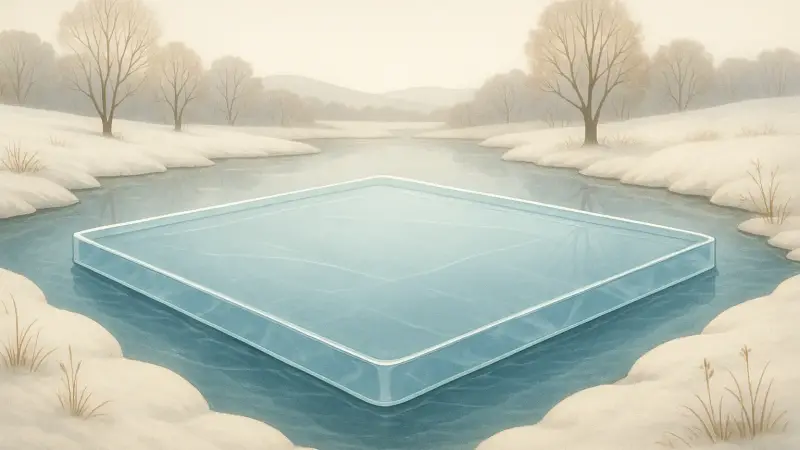

On some winter mornings, a pond looks less like ice and more like a sheet of window glass dropped onto the water. This isn’t one single famous pond. People report it on small kettle ponds in New England, on sheltered bays of Lake Baikal in Russia, and on quiet inlets in Finland and Sweden. The “overnight” part is usually just how it feels, because the change can happen during a short calm stretch after sunset. The core mechanism is simple: ice can freeze without trapping many bubbles or cracks if the water is still, clean, and the freeze happens steadily, layer by layer.

What “clear ice” actually is

Most pond ice is cloudy because it contains lots of tiny air bubbles and small crystal boundaries that scatter light. Clear ice is more uniform. It has fewer bubbles, fewer impurities, and fewer abrupt changes in crystal structure. Light passes through it instead of bouncing around, so the pond looks dark underneath, with leaves and stones visible like they’re under a lens.

It also tends to feel “perfect” because the surface can be remarkably smooth when wind doesn’t rough it up while it’s forming. A skim of ice can lock in a mirror-flat surface if the pond is sheltered by trees or banks. That smoothness is separate from clarity, but the two often appear together, so people treat them as the same thing.

How it can form so fast

The speed comes from the first thin layer. Once the top millimeter freezes, it changes the heat flow. Water underneath is insulated from wind mixing, and the ice surface radiates heat into the cold night sky efficiently. If air temperatures drop well below freezing and the night stays calm, the ice can thicken quickly enough to look “new” by morning, even if the pond had been hovering near freezing for days.

The steadiness matters more than the absolute cold. A night with a smooth, continuous temperature drop can create clearer ice than a colder night with gusty wind, snow flurries, or a brief thaw. Those interruptions encourage trapped bubbles, stress cracks, and a rougher texture that turns the surface milky.

Still water, fewer bubbles

Air bubbles are the usual culprit. If water is churning, it mixes in air, and bubbles get caught as ice crystals knit together. In a quiet pond, the surface water can be almost motionless. That gives dissolved gases time to escape before they are sealed in. When ice forms slowly and evenly from the top down, gases can also be pushed ahead of the freezing front rather than trapped inside it.

A specific detail people overlook is what happens right at the start: the very first skim can form when the surface is already “de-gassed” compared with deeper water, especially after a calm, cold evening. That top layer has been in contact with the air and can lose some dissolved gas. If that skim forms before wind returns, it can be unusually bubble-free, and the clarity looks shocking because the ice is also very thin.

Why snow and slush ruin the effect

Clear ice needs an exposed surface. Snow falling onto new ice acts like a blanket and changes the way the next layers freeze. Even a dusting can be enough. Snow insulates, keeps the ice warmer, and slows the clean, directional freeze that makes uniform crystals. It also introduces grit and air pockets that turn into white speckling.

Slush is another clarity killer. If a thin ice sheet gets flooded by water (from a heavy snowfall pushing it down, or from waves washing over it), that wet snow refreezes as a porous layer full of tiny voids. The result is “white ice,” which is strong enough in places but never looks like glass.

Why it looks darker than you expect

When ice is clear, the pond often looks almost black. That surprises people who expect “transparent” to mean bright. The darkness is mostly the water itself absorbing light, plus whatever is on the bottom. If the pond is deep enough, or the bottom is dark mud, there isn’t much light bouncing back. Cloudy ice, by contrast, reflects and scatters light, so it looks white even when the water beneath is dark.

This is why sheltered, windless spots are the ones that get talked about: a small inlet, a corner behind reeds, or a shaded pond with little inflow. It’s not that they freeze differently in principle. They just avoid the small disturbances—breeze ripples, early snow, slushy flooding—that add texture and turn an ordinary freeze into a pale, noisy surface instead of a clean sheet.