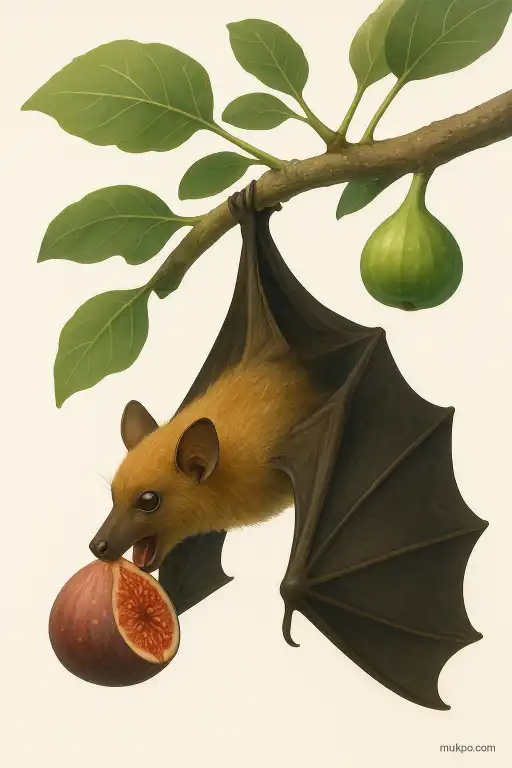

A bat that behaves like a gardener

People rarely ask where a fig tree “starts” in a rainforest. Not the species. One specific tree. In places like Costa Rica and Panama, some fig trees may get an unusual assist from a small bat called Artibeus watsoni, Watson’s fruit-eating bat. The basic idea is simple. The bat eats ripe figs, carries the seeds, and drops them in spots where they can actually sprout. But it doesn’t always drop them randomly. It often returns to the same kinds of sheltered roosts and feeds there, leaving seed-rich droppings that can turn those roost sites into little fig nurseries.

How the “planting” happens

This bat doesn’t bury anything. It can’t push seeds into soil the way a squirrel might. The “planting” is mostly about delivery and placement. After feeding, it defecates seeds that are still viable. Those seeds land stuck to damp leaf surfaces, in moss, or in the debris that collects where leaves overlap. Figs are famous for starting life as epiphytes, germinating on branches or in crotches of trees before sending roots downward later. A seed that lands on the forest floor often dies in the dark. A seed that lands up in the canopy sometimes gets a chance.

The overlooked detail is time. Fruit bats digest quickly, and that shapes where seeds end up. If a bat eats at one tree and then immediately flies to a roost to chew and rest, most of the seeds from that meal may be deposited right around that roost. That creates a repeatable pattern. It’s less like scattering confetti and more like dropping seeds at a few favored stops, night after night.

Why a rolled leaf matters more than a hole in a tree

Artibeus watsoni is known for using “tents” made from leaves. It bites along the veins of broad leaves so they fold into a little shelter. These leaf tents are temporary. They can last days to weeks, depending on weather and how quickly the leaf deteriorates. They also hang in the understory or lower canopy, exactly the zone where light is better than the ground but humidity is still high. That’s a surprisingly good seed-starting environment for plants that can germinate above ground.

A concrete situation looks like this: a bat feeds at a fruiting fig, then flies to its tent, where it’s safer from many predators. It chews, rests, and drops seeds onto the leaf surface below. Rainwater and condensation keep those seeds damp. Bits of dust, insect frass, and tiny scraps of plant matter collect in the folds. Over time, you get a tiny pocket of “soil” on a leaf. That pocket is easy to miss if you’re looking for seedlings on the ground.

Is it really farming, or just a side effect?

Calling it “farming” depends on how strict you are. The bat is not tending seedlings, removing competitors, or defending a patch. It’s also unclear how often a seed dropped at a tent actually becomes a mature fig. Many seedlings fail. Leaves fall. Branches break. Drought hits. But the repeated behavior does something important: it increases the odds that fig seeds get delivered to the exact kind of perch where figs can start. That’s a bias, not an accident.

There’s also a feedback loop that can look intentional from the outside. Fig trees are a reliable food source in many tropical forests, and different fig species fruit at different times. A bat that helps create new fig starts might, over long timescales, contribute to keeping figs common in its home range. The bat isn’t planning for next year. The ecology can still end up looking like “planting,” because the same choices keep being made: eat, fly to shelter, rest, and drop seeds.

What researchers actually look for in the field

To connect a bat’s roosting habits to new fig plants, researchers look for several things at once. They map tent sites, check what’s underneath them, and identify seedlings. They also examine droppings and spit-out pulp to see which seeds are being moved, and whether those seeds can germinate. Some studies use fine mesh or collection sheets under roosts for a short period, because rain and insects can erase evidence quickly. A tent can look empty even if it was used heavily the night before.

The small, easy-to-overlook complication is that many animals move fig seeds. Birds do. Other bats do. Monkeys do in some regions. So when a fig seedling pops up in a strange place, it’s rarely possible to credit one individual animal with certainty. What can be shown more cleanly is a tendency: certain bats repeatedly create seed “hotspots” around their shelters, and those hotspots sometimes line up with where fig seedlings are most likely to appear.