A simple question people rarely ask

When a meteorite lands, people usually talk about the flash, the crater, or the weirdly heavy rock you can hold in your hand. The quieter question is what’s inside it at the molecular level. There isn’t one single “meteorite” story here, because different stones preserve different chemistry. Scientists compare famous samples like the Murchison meteorite (Australia, 1969), Tagish Lake (Canada, 2000), and fragments linked to asteroid Ryugu returned by JAXA. In the lab, they dissolve tiny chips and separate the contents. Then they look for organic molecules and their isotopes, because those patterns can point back to the chemical conditions in the early solar system.

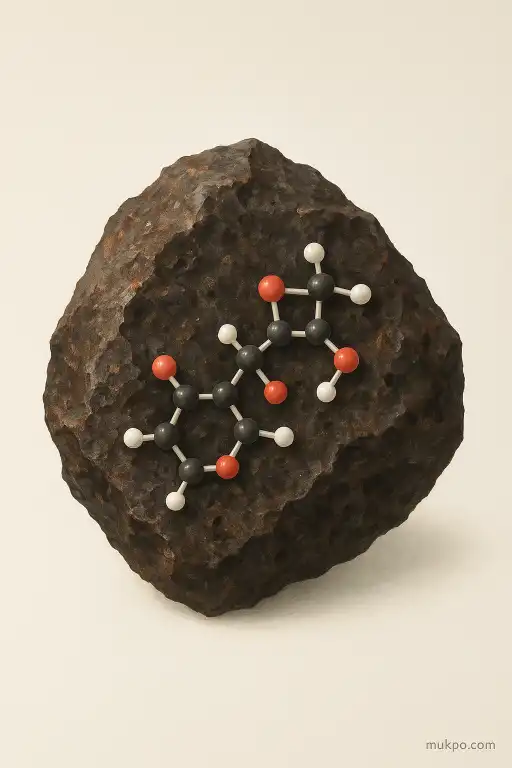

What “organic molecules” means in a space rock

In this context, “organic” doesn’t mean biological. It means carbon-based molecules: amino acids, carboxylic acids, hydrocarbons, and nitrogen-bearing compounds. Some meteorites also carry sugar-related molecules and components that can be turned into nucleobases under certain reactions, though what’s present and how confidently it’s identified can vary by sample and method. The key point is that these molecules sit inside a mineral matrix that formed very early, before planets were fully assembled, and they can survive because parts of some meteorites never got hot enough to erase them.

One detail people often overlook is how easily modern contamination can mimic “space organics.” A meteorite that sits on wet ground can pick up Earth microbes and plant material fast. That’s why curators cut into the interior, use clean tools, and compare blanks and control samples. Even then, researchers lean hard on isotope ratios, because Earth life tends to cluster around certain carbon and hydrogen isotope values, while extraterrestrial organics often look measurably different.

How those molecules form before planets are finished

Early solar chemistry happened in more than one place. Some organics likely formed in cold interstellar ice before the Sun existed, then got inherited by the forming solar system. Others formed inside the solar nebula gas and dust disk. And a lot of the chemistry people measure in carbon-rich meteorites happens later, inside the meteorite’s parent body, when ice melted and liquid water circulated through rock.

That parent-body processing matters because it creates specific families of molecules. Amino acids, for example, can be made through reactions involving aldehydes or ketones, ammonia, and hydrogen cyanide in water. The exact mix depends on what starting compounds were available and on temperature, pH, and time. If a meteorite shows many related molecules in a pattern, researchers treat that as a clue that the rock didn’t just “collect” organics; it hosted reactions that built and reshaped them.

What isotopes and “handedness” say about early conditions

Two tools show up again and again: isotopes and chirality. Isotopes are atoms of the same element with different masses, like carbon-12 versus carbon-13, or hydrogen versus deuterium. When scientists find organics enriched in deuterium or with distinctive nitrogen-15 signals, they connect that to low-temperature chemistry and radiation-driven reactions in ices. Those isotope fingerprints can survive later alteration, so they act like tags that tell you something about where the ingredients came from and how cold some steps must have been.

Chirality is the “handedness” of certain molecules, including many amino acids. Life on Earth uses mostly left-handed amino acids, but non-living chemistry tends to make left and right in equal amounts. Some meteorites show small but real imbalances for certain amino acids. How those imbalances arise is still debated. Possible mechanisms include polarized ultraviolet light acting on ices or selective processes during aqueous alteration. What matters for early solar chemistry is that the imbalance, when it holds up under contamination checks, implies reactions were happening in environments with physical biases, not just random mixing.

Why different meteorites tell different chemical stories

Not all meteorites are equally talkative. Carbonaceous chondrites tend to carry the richest organic inventories, while many stony meteorites have been heated enough to wipe out fragile compounds. Even within carbonaceous groups, the degree of water alteration varies. Tagish Lake, for instance, is often discussed because it was collected quickly from a cold environment, reducing some contamination pathways, and it shows complex organics alongside evidence of extensive alteration. In contrast, samples returned directly from asteroids, like Ryugu material, can be handled under stricter curation and offer a cleaner read on what was there before Earth exposure.

Another overlooked detail is that minerals can “lock in” chemistry. Certain clays and carbonates form during water-rock interaction and can trap organics in pores or on surfaces, which changes what survives for billions of years. So when researchers compare meteorites, they aren’t just comparing lists of molecules. They’re comparing histories: how much water moved through, how long it lasted, whether heat spikes happened, and whether the rock stayed sealed or got cracked open. That’s why the organic molecules are useful. They don’t just exist in the meteorite. They carry the marks of the environments that made and modified them.