Salt looks dead. It’s the thing people pour on ice or rub into food to stop microbes, not help them. And yet researchers have found living microbes trapped inside salt crystals from places like Death Valley in California and the salt mines of the Austrian Alps. It isn’t one single famous discovery site, because similar finds show up wherever old brines get locked into minerals. The core trick is surprisingly physical: as a salt crystal grows, it can seal off tiny pockets of liquid brine inside it. If a microbe ends up in one of those pockets, it isn’t “in dry salt” at all. It’s in a micro-aquarium.

Where a “microbe inside salt” actually lives

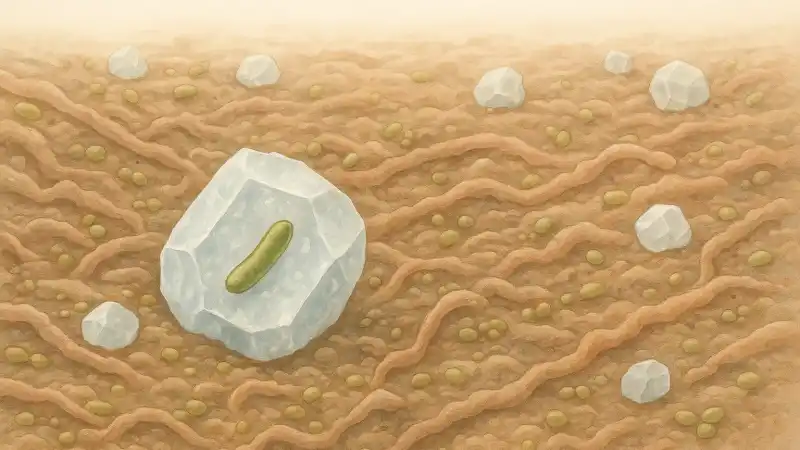

When people say “inside a salt crystal,” they usually mean inside a fluid inclusion. That’s a microscopic cavity filled with concentrated brine that got trapped during crystallization. Under a microscope, these inclusions can look like little droplets or angular bubbles. The overlooked detail is that many inclusions are not isolated forever. Some have hairline fractures or tiny channels that can slowly exchange water and gases with the outside, especially if the crystal is stressed, warmed, or slightly dissolved and re-grown.

This matters because it changes what “survival” means. A cell in a sealed droplet has to live on what’s in there. A cell in a droplet that can trade a bit with its surroundings can sometimes get periodic refreshes of water or trace nutrients. That difference is hard to see without careful imaging, so claims about how long a microbe “stayed alive” can vary depending on how well the inclusion was characterized.

What kinds of microbes show up in salt crystals

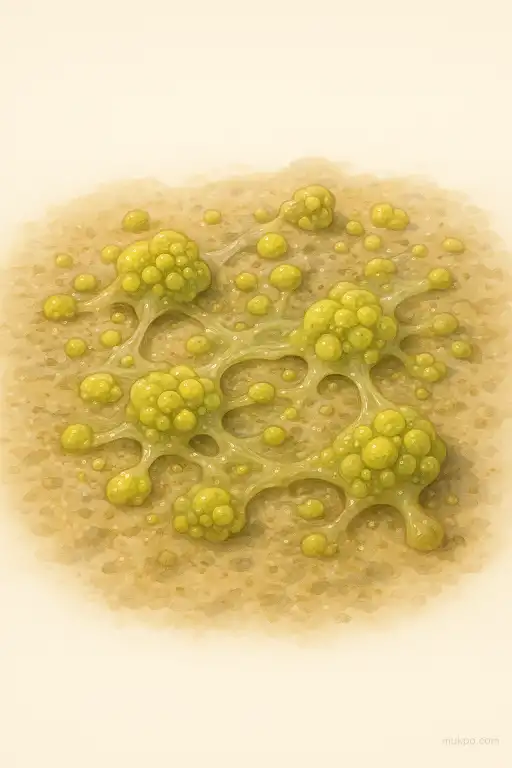

The organisms most often discussed are extreme halophiles, especially haloarchaea. These are microbes that prefer very salty environments and don’t just tolerate salt as a stress. Some make reddish pigments, which is why salt ponds can turn pink. Others found in salt deposits are bacteria adapted to high salinity, and sometimes dormant forms like spores are part of the story.

It’s also worth separating “found in salt” from “proved to be ancient.” In some studies, cells are observed in inclusions and then cultured or detected with genetic methods. In other cases, researchers debate whether modern contamination could have entered later through cracks. Salt seems solid, but it can creep, fracture, and heal over time. That makes the microbiology fascinating and also messy.

The main survival problem: water, not food

Life needs liquid water. High salt creates a harsh water-balance problem because it pulls water out of cells. Extreme halophiles deal with this by matching the outside. Some accumulate potassium and other ions inside the cell to balance osmotic pressure. Others pack their cytoplasm with “compatible solutes” that don’t interfere as much with proteins. Their enzymes and cell structures are built to function in that salty chemistry, not in fresh water.

Inside a fluid inclusion, the brine can stay liquid over a wide range of conditions because it’s so concentrated. That’s the quiet loophole. The crystal can be dry to the touch, but the microbe is sitting in a stable, salty liquid environment. The limitation is volume. These inclusions are tiny, so a cell can quickly run out of usable nutrients or build up waste unless it slows down drastically.

How microbes stretch time in a sealed brine pocket

In extreme conditions, many microbes shift into very low metabolic states. They don’t “sleep” in a magical way. They just reduce activity to the minimum needed to repair occasional damage. Salt crystals can also block a lot of incoming radiation and dampen rapid temperature swings, which reduces some kinds of stress. If the inclusion is in halite (sodium chloride), the crystal is transparent, but it still changes the light and radiation environment compared to an exposed wet surface.

One more overlooked constraint is oxygen. In a tiny brine pocket, oxygen can be used up and not replenished if the inclusion is sealed. Some halophiles can handle low oxygen or use alternative chemistry, but it shapes what can persist. It’s one reason why “we revived it” claims depend heavily on the exact organism and on whether the inclusion was truly closed or had micro-pathways.

What scientists can and can’t claim from these finds

There are solid observations: microscopic brine inclusions exist, cells can be seen inside them, and salt environments like solar salterns regularly trap microbes as crystals grow. There are also real laboratory results where halophiles are cultured from salt samples. But the age question is often the slippery part. Dating the salt layer is not the same as proving the cell inside an inclusion has been continuously alive since that layer formed.

Still, the basic survival logic holds even without the most dramatic timelines. If a microbe ends up sealed in a briny droplet, it has liquid water, high salinity it’s already adapted to, and a physically protected space. It’s a strange kind of habitat, small enough to fit inside a crystal you could crush between your fingers.