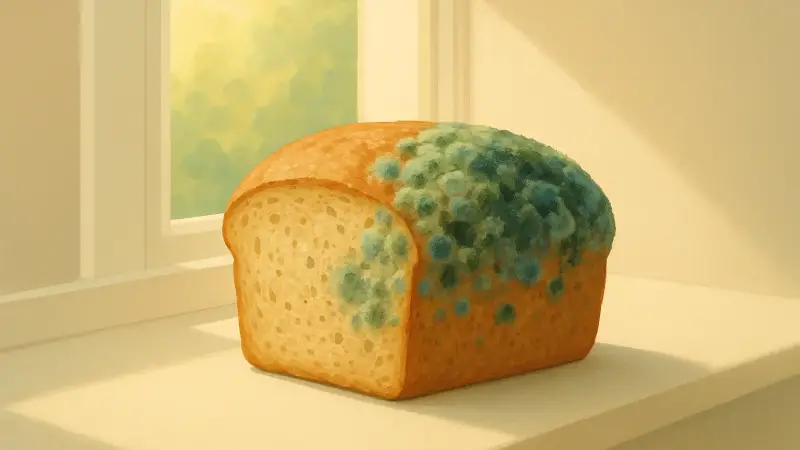

People notice it in lots of ordinary places, not one specific town or event. A loaf left near a sunny window in an apartment in New York, a kitchen in London, or a flat in Tokyo often shows mold sooner than the same bread left in a darker cupboard. It feels backwards, because bright sun seems like it should “clean” things. But bread mold isn’t reacting to light the way a plant does. It’s reacting to the little climate the windowsill creates: warmer air, changing moisture, and a surface that swings between humid and dry. Those shifts can push bread into the conditions molds like best.

Sunlight changes the bread’s microclimate

A sunny windowsill is usually warmer than the rest of the room. Even in winter, glass can trap heat and create a small “hot zone” right at the ledge. Mold growth tends to speed up as temperatures move from cool toward mild and warm. Not hot enough to kill anything, just warm enough to make metabolism faster. That’s why the spot by the glass can be different from the counter a few feet away.

There’s also a daily rhythm. Sun hits the bread for a few hours, then it cools down again at night. That cycling matters because it changes how water moves in and out of the bread and any packaging. A stable, cool pantry doesn’t do that as much.

Moisture moves in ways people don’t notice

Mold needs available water. Bread feels “dry,” but it holds plenty inside, especially sandwich bread. On a windowsill, warmth can pull moisture from the interior toward the surface. If the bread is in a bag, that moisture can condense on the inside when the temperature drops later. A thin film of water on plastic doesn’t look dramatic, but it can keep the bread surface damp for hours.

One overlooked detail is how often the “sweating” happens right where the bag touches the loaf. The contact points can stay wetter than the exposed parts. Those are common spots where the first fuzzy patch appears, because the mold has both food and steady moisture right there.

The bag can turn sun into a mini incubator

Many loaves sit in clear plastic. Plastic doesn’t breathe much, so humidity builds up. Add sunlight, and the air inside warms. Warm air holds more water vapor, so it can load up with moisture from the bread. Then when the sun moves or the room cools, that same moisture can fall out as condensation. The result is repeated humid spikes, which molds generally tolerate well.

People also miss the effect of the windowsill itself. The ledge is often cooler than the room air when it’s cold outside, even if sunlight warms it part of the day. That temperature difference between plastic, bread, and the surface underneath is a recipe for tiny, localized condensation. It’s the same reason windows fog.

Sunlight doesn’t reliably stop common bread molds

Direct sunlight can damage microbes, but the details matter. Many bread molds spread as spores, and spores are built to survive stress. Also, the light has to actually reach them. If spores are on the underside of a slice, in a crease, or under the bag fold, the exposure is low. Glass can block some ultraviolet light, and the spectrum that gets through varies by window type and coatings. So the “disinfecting” side of sunlight is often weaker than people assume.

Meanwhile, the warming and moisture effects are consistent. So the net result can still be faster visible growth, even though there’s light present. The bread isn’t being sterilized. It’s being kept closer to the conditions that let surviving spores wake up and spread.

Why the first spot of mold often shows up where it does

Mold rarely appears evenly across a loaf. It starts where conditions are best and where a spore happened to land. On a windowsill, that’s often the side facing the room rather than the side pressed against colder glass, but it varies with airflow and whether the bag is sealed tight. If the bread is sliced, the cut faces give mold a head start because they expose soft interior crumb instead of a drier crust.

A concrete example is a loaf left in its bag on a bright kitchen ledge above a radiator. The warmth from below and sun from the side can keep the baggy air humid, and the first mold spot may show up where two slices touch and the plastic lies against them. That little sheltered, slightly damp contact zone is easy to overlook until the green fuzz shows.