Walk through a corn field on a hot afternoon and you can feel how hard the plants are working. This isn’t one single place or one single event. It shows up in heat waves in the U.S. Midwest, in irrigated wheat areas of northern India, and in parts of Australia during hot, dry spells. One reason hot days bite so sharply is a built‑in process called photorespiration. It happens in the same cells where plants try to turn CO₂ into sugars. When temperatures rise and CO₂ inside the leaf drops, the machinery that should be fixing carbon starts grabbing oxygen instead. The plant still burns energy, but it gets less growth out of the light it captured.

Photosynthesis has a messy side reaction

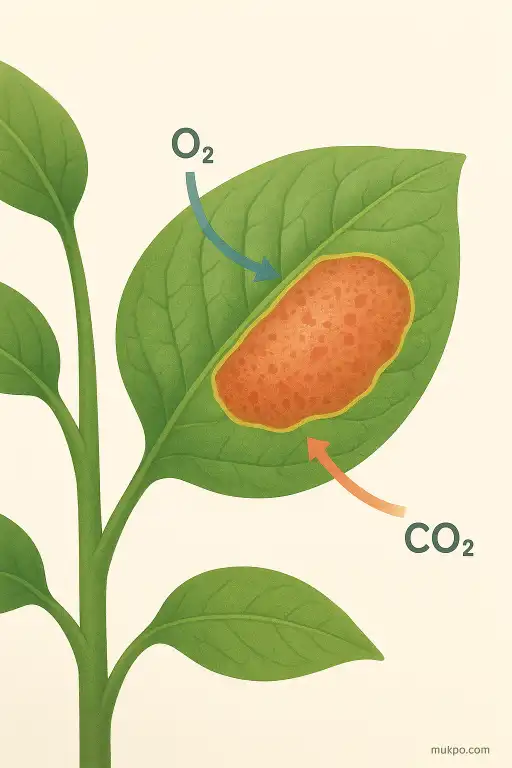

Most of the familiar story is simple: light energy helps a plant pull CO₂ from the air and build carbohydrates. The messy part starts with Rubisco, the key enzyme that attaches CO₂ to a carbon chain. Rubisco can also attach O₂. It is not a rare accident. It is a regular competing reaction that becomes more common under certain conditions.

When Rubisco grabs oxygen, the plant produces a compound it can’t use directly in the normal sugar-making pathway. The plant then has to run a salvage route—photorespiration—to recover part of the carbon. That recovery costs energy and releases CO₂ along the way. So some of the carbon the leaf just took in gets sent right back out.

Heat and closed stomata set the trap

Hot days push leaves toward water loss. Plants respond by closing stomata, the tiny pores that let CO₂ in and water vapor out. Closing them slows dehydration, but it also limits CO₂ entry. Inside the leaf, CO₂ falls while O₂ rises because photosynthesis is still producing oxygen. That shifting ratio favors the oxygen-grabbing reaction.

Temperature adds another nudge. As it gets warmer, Rubisco’s selectivity for CO₂ over O₂ generally drops, and photorespiration speeds up. There is also a physical detail people often overlook: warm water holds less dissolved CO₂, and diffusion inside a leaf becomes a bigger bottleneck when stomata are partly shut. The leaf can be surrounded by air with plenty of CO₂, yet the enzyme “sees” much less of it.

Photorespiration spends fuel and gives less back

The salvage pathway is not free. It consumes ATP and reducing power that could have gone into making sugars. It also ties up enzymes and cellular transport steps. The net effect is that the same sunlight produces fewer usable carbohydrates, even though the leaf may still look bright green and active.

A concrete example helps. In a soybean field during a heat wave, leaves may warm well above the air temperature if the air is dry and wind is low. Stomata often tighten, CO₂ inside the leaf drops, and photorespiration rises. The plant is still absorbing light, still moving electrons, and still spending energy. But more of that effort goes into recycling rather than building new biomass.

Some crops avoid it better than others

Not all crops are hit the same way. Many major crops—wheat, rice, soybeans, potatoes—use “C3” photosynthesis, where Rubisco operates in an environment close to the surrounding leaf air spaces. C3 plants tend to show stronger photorespiration under heat and low internal CO₂.

Others, including maize (corn) and sugarcane, use “C4” photosynthesis. They run a CO₂-concentrating step that delivers higher CO₂ levels to Rubisco in specialized cells. That setup suppresses photorespiration, especially in hot, bright conditions. It doesn’t make C4 crops immune to heat stress, but it changes which weak points dominate: enzymes can still fail at extreme temperatures, and water limits still matter, yet the oxygen-grabbing problem is reduced.

Why it shows up as lower yield, not instant damage

Photorespiration is a drain that often looks like “nothing happened” on any single day. Leaves may not scorch. Plants may stay upright. But over many hot afternoons, less carbon is stored, so there is less material to put into grain, tubers, or fruit later. The timing matters. Heat during flowering or grain filling can stack the carbon loss on top of other temperature-sensitive steps in reproduction.

There is also a quiet measurement detail behind the scenes: the leaf’s temperature can be several degrees higher than the weather report, because the plant’s own evaporative cooling weakens when stomata close. That means the chemistry in the chloroplast is often operating at a hotter temperature than people assume when they hear “35°C day.” That extra few degrees is enough to tilt Rubisco further toward oxygen and make the day feel longer for the crop.