How a key becomes a museum object

People lose keys in the most ordinary ways. A pocket rips. A bag gets set down for one minute. A ring slips off while someone is paying for coffee. Instead of heading straight to the trash, some of those keys end up collected and displayed, sometimes in the thousands, with no name attached and no door to return to. This isn’t one famous building that everyone agrees is the place. It pops up in different forms, like the Key Museum inside Japan’s Key Station at the Notojima Glass Art Museum complex in Ishikawa Prefecture, or local “found key” displays that start in police stations, transit lost-and-found rooms, and community museums.

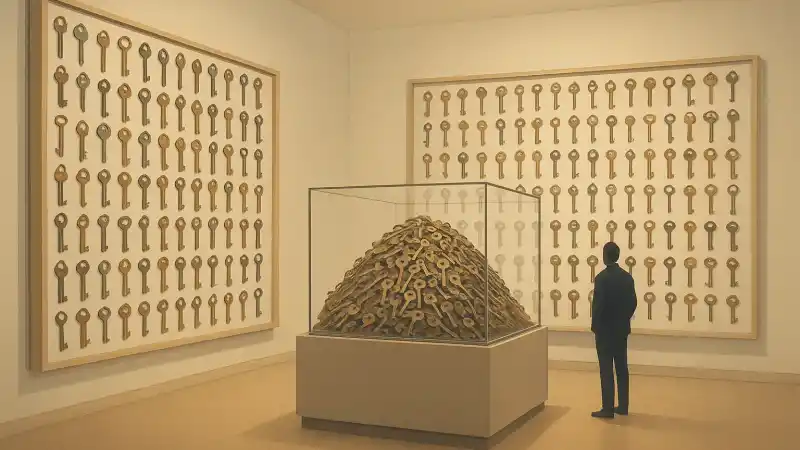

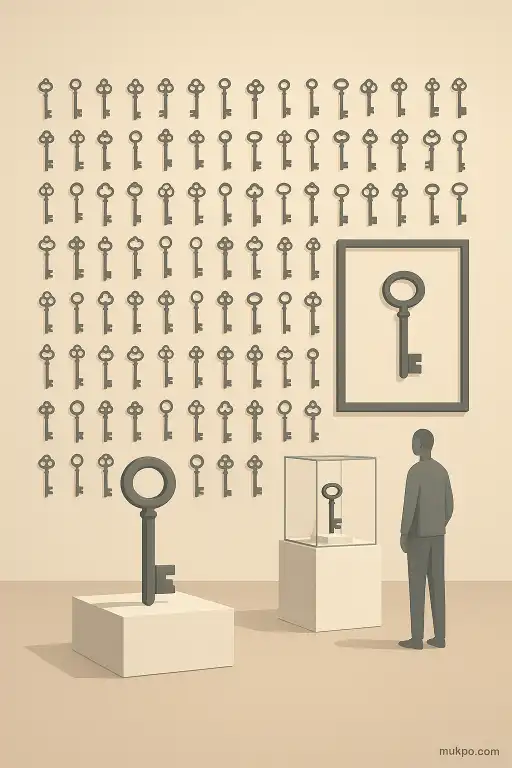

What you actually see when you walk in

The visual effect is usually the first surprise. Thousands of small objects don’t read as “thousands” until they’re arranged. Keys get pinned behind glass, hung on boards, or grouped by shape and age. Modern house keys sit next to old skeleton keys. Padlock keys show up in batches. There are often oddities: a key taped to a note that says “found by the river,” a keychain from a closed-down business, a key with a snapped tooth that probably stopped working before it was even lost.

One detail people overlook is how much information is accidentally on the keyring, not the key. A gym fob, a transit pass, a tiny loyalty tag, or a branded keychain can reveal where someone went every day. Some displays avoid showing those attachments for privacy reasons. Others keep them because it’s part of how the item was found, even when the owner is anonymous.

Where all those anonymous keys come from

A big pile of lost keys usually starts with an institution that already receives them. Police “found property” counters accumulate keys constantly. So do rail operators and bus depots. Keys are common because they’re easy to drop and hard to identify. A wallet might have an ID card. A phone can ring. A loose keyring is silent. If nobody claims it by a retention deadline, the organization has to decide what happens next, and the options vary by place and policy.

Some collections come from deliberate drives. A museum might ask locals to donate old keys from demolished houses or shuttered factories, which creates a different kind of “lost.” The keys aren’t misplaced. Their doors are gone. They still end up anonymous because the original context has vanished, and the object is now only a piece of hardware with an unknown story attached.

Why displaying them changes how people treat them

Behind glass, a key stops being a problem to solve and becomes something to look at. That shift matters. Staff can label by what they can prove—approximate era, material, type of lock—without pretending they know the owner. Visitors tend to scan for patterns: which shapes repeat, how key blanks evolve, how quickly “unique” keys start to look like each other when there are enough of them. It’s a quietly useful way to notice how standardized security hardware is, even across decades.

These displays also run into a basic tension. The whole point of a key is access. So a museum has to be careful about not enabling access. That’s why many collections either don’t show identifying tags up close, don’t give exact “where found” locations, or keep modern keys in a way that can’t be easily copied. The exhibit is often less about the lock and more about the social life of the object: how it gets carried, dropped, found, and then absorbed into an institution.

The quiet logistics behind a wall of keys

A thousands-of-keys display is, first, a storage system. Keys are small, sharp, and prone to tangling. They corrode. Keyrings rust. Labels fall off. If the museum treats them as found property, it has to track what came from where, at least internally, and what legal status it has. If it treats them as donated artifacts, it still has to decide what counts as “the object.” Is it the key alone, or the whole ring with the plastic supermarket tag and the tiny screwdriver someone clipped on?

And then there’s the unavoidable human moment: someone stands in front of the case and thinks they recognize one. Most of the time they can’t be sure. Keys are meant to be copied and replaced. That’s why the exhibit works at all. It’s a room full of objects designed to be interchangeable, each one tied to a missing lock that almost nobody can name anymore.