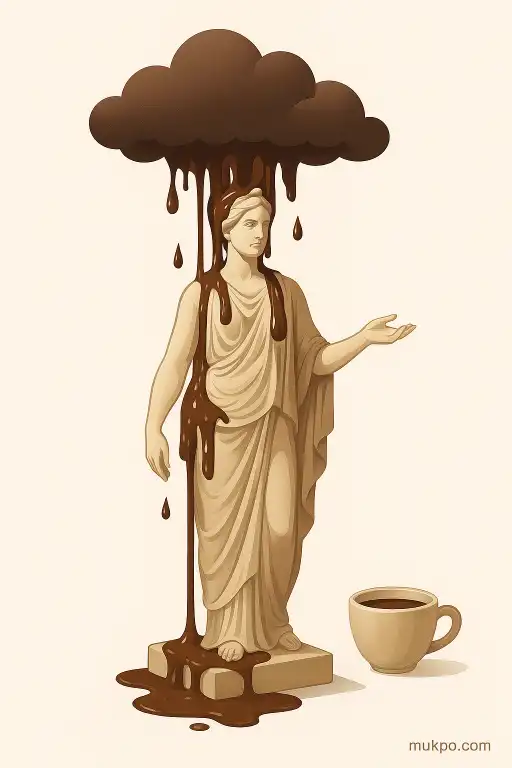

A strange thing to see after a storm

After a hard rain, people expect puddles, grit, and that dull rinse-water running off everything. Seeing brown liquid bead up on a statue and drip down its surface looks wrong on instinct. Sometimes it even smells like coffee. This isn’t one single famous monument that always does it. Reports pop up in different places, usually around cafés, markets, or streets where food and drink are constant. The basic mechanism is usually ordinary: stormwater hits a surface, washes through residue and tiny particles, then exits at a few predictable points—often the lowest seams, bolt holes, or drainage channels built into the sculpture’s base.

Why the runoff can look like brewed coffee

“Coffee-colored” runoff doesn’t need any coffee in it. Rainwater is good at picking up tannin-like compounds and fine soot. If the statue sits under trees, leaf litter and pollen can stain water a dark tea color. Urban grime does the rest. Diesel soot, tire dust, and roofing particles collect in thin films. A storm mobilizes them all at once, and the first flush looks dramatically darker than what follows.

It also helps that many statues are light stone, pale metal, or painted surfaces where contrast is high. A thin brown stream stands out immediately. People often overlook that the darkest water tends to appear at the start of rainfall or right after a dry spell, when there’s been more time for dust and sticky residues to build up. The “coffee” effect can fade within minutes, even though the rain continues.

The hidden plumbing inside and underneath

A lot of public sculpture is not a solid block. Hollow cast bronze is common, and stone pieces can be assembled from multiple slabs. Water gets inside through seams, hairline cracks, or around attachments like plaques and arms. To prevent freeze damage and internal corrosion, fabricators often include weep holes and internal drain paths. When the wind drives rain into those openings, the statue “oozes” from a few small exit points instead of shedding water evenly.

A specific detail people usually miss is how much the base matters. Pedestals frequently have a recessed cap, a hidden gutter, or a narrow gap where the statue meets its mounting plate. That edge traps water and concentrates grime. When it finally drains, it drains in one or two ribbons. If those ribbons run over a textured surface—chisel marks, patina streaks, or grime lines—they darken fast and look thicker than they are.

When it really can involve coffee

Sometimes there is actual coffee in the story, just not in a magical way. If a statue is near outdoor seating, people spill drinks and dump cups. Coffee dries into a sticky film that traps dust. The next storm rehydrates it and carries it downward. The smell can linger because warm air after rainfall pushes volatile compounds off wet surfaces, and noses are sensitive to it at close range.

Another route is building drainage. A downspout or scupper can be positioned so overflow hits the statue or its plinth. If that roof runoff has passed through a gutter full of decomposing leaves, it can come out dark brown and organic-smelling. To an observer, it looks like the statue is producing the liquid. The source is upstream and hidden, so the timing feels uncanny: storm, then “coffee.”

Color, expectations, and the way people report it

The reason this gets described as coffee, specifically, is partly social. Coffee is a familiar reference and a familiar color. People already associate statues with fountains and “secret mechanisms,” so a concentrated brown drip becomes a story quickly. Photos rarely capture smell, thickness, or how fast the flow clears, which are the details that would separate stained stormwater from something deliberately pumped.

It also doesn’t take much liquid to look dramatic. A few ounces running down a face or hand reads like oozing, especially if it follows the same path every time. Water finds the same low point, again and again. That repeatability makes it feel intentional, even when it’s just gravity working through a couple of seams and a surprisingly dirty surface.