How one laboratory ended up on the street

It’s strange how a technical act can spill into ordinary city life. In 1903, a small brown dog was used in a physiology demonstration at University College London. The animal’s suffering, and the question of whether it was properly anesthetized, didn’t stay inside the lab. It turned into pamphlets, meetings, and arguments in the open. Within a few years it became something you could bump into on your way home, because the dispute ended up anchored to a physical object in Battersea: a memorial statue to the dog that people fought over in public.

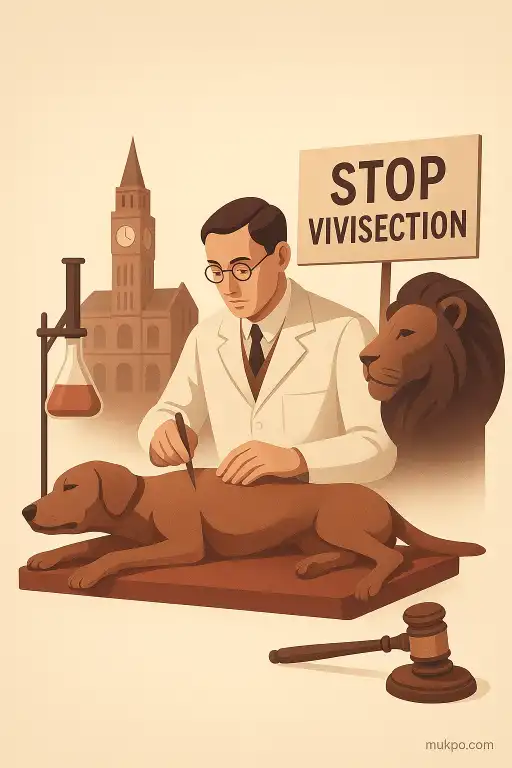

The vivisection and the argument about what happened

The demonstration that triggered the storm is often described as a “vivisection,” but what matters is the allegation around it. Two Swedish activists, Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Leisa Schartau, attended demonstrations in London and later published accounts accusing researchers of operating on a conscious or insufficiently anesthetized dog. The scientists involved denied this, and the dispute became a legal and public-relations battle rather than a single agreed set of facts.

That uncertainty is part of why it escalated. The antivivisection side treated the dog as proof of cruelty that slipped through the cracks of regulation. The medical side treated the story as a damaging misrepresentation of routine scientific work. And because the claim hinged on what observers believed they saw in a teaching room, it was easy for people to talk past each other while still feeling certain.

Why a statue in Battersea became a fuse

In 1906, a memorial to the “Brown Dog” was erected in Battersea Park. It didn’t just mourn an animal. It accused. The inscription condemned what it called torture and named “men and women of England” as responsible for allowing it. That meant the statue wasn’t neutral art. It was an argument bolted into a public space, with words that medical students could read as a direct provocation.

A detail people often overlook is how practical the statue’s presence was as a target. It was outdoors, reachable, and easy to rally around on short notice. A meeting in a hall can dissolve. A statue stays put. It also sat in a working-class area with strong local politics, so it landed in a neighborhood that already had networks for organized gatherings and counter-gatherings.

The riots: medical students, policing, and public order

The “Brown Dog riots” weren’t one continuous riot so much as repeated confrontations. Groups of medical students tried to damage the memorial and disrupt meetings linked to antivivisection campaigners. Their opponents included local residents, trade unionists, socialists, and feminists who saw the attacks as bullying and a threat to public space. The clashes drew police protection for the statue, which only made it more visible as a contested site.

What tends to get lost is how much of this was about status and authority, not only animal welfare. Medical students were training for a profession that claimed social legitimacy through science and expertise. Being publicly labeled “torturers” by a park monument was humiliating, especially in an era when street politics and heckling were common tools. On the other side, protecting the statue became a way to push back against elite institutions that seemed untouchable.

What the fight revealed about Edwardian London

The conflict sat at the junction of several fast-moving Edwardian arguments: what science was allowed to do, who got to observe it, and whether “progress” excused suffering. Britain already had the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 regulating animal experiments, but the Brown Dog controversy made regulation feel either meaningless or oppressive, depending on where you stood. A laboratory procedure became a proxy for how much trust people owed institutions.

It also showed how activism worked when newspapers, pamphlets, and public meetings were the main amplification tools. A contested narrative could travel quickly, especially when it featured a single vivid victim and a named place like University College London. And once the story was nailed to a park statue, it didn’t matter that some details were disputed. People could point to it, argue in front of it, and treat its survival or destruction as a win that felt concrete.