You can watch posture change decision making in places as ordinary as a job interview in London, a poker table in Las Vegas, or a hospital break room in Tokyo. There isn’t one defining moment or single famous case. It’s a repeatable, small shift. The core mechanism is that posture changes the body’s signals—breathing depth, muscle tension, gaze angle, and how exposed or protected you feel—and those signals feed into how the brain estimates risk, status, and effort. People often think decisions start in the head and posture follows. A lot of the time, the loop runs both ways.

Posture is part of the information your brain uses

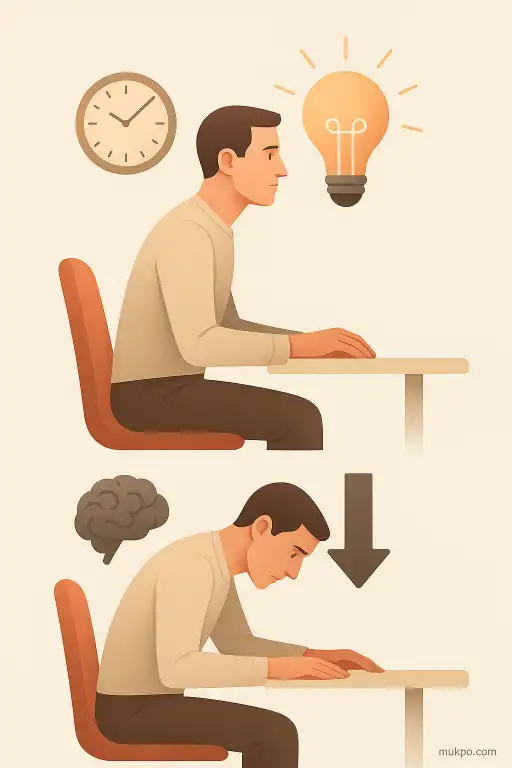

Decision making depends on quick guesses: how safe a situation is, how much energy something will cost, whether you can handle conflict, whether waiting is worth it. Posture quietly changes those guesses because it changes bodily inputs the brain treats as data. A slumped position often comes with shallower breathing and a narrower visual field. An upright position usually comes with more chest expansion and a steadier head angle. Those differences can nudge choices toward avoiding effort, deferring, or taking a smaller bet, even when the facts on the table haven’t changed.

A specific detail people overlook is jaw and tongue tension. When someone braces their jaw or presses the tongue hard against the roof of the mouth, it can raise overall muscular “readiness” without them noticing. That readiness can be read internally as urgency. Under urgency, people tend to favor faster decisions, accept simpler explanations, and switch from weighing options to picking one that ends the discomfort.

Breathing shifts the sense of risk and time

Breathing is tightly linked to posture, especially in the ribs and diaphragm. When posture compresses the torso, breaths often get shorter and higher in the chest. That pattern is commonly paired with heightened arousal. It doesn’t create fear out of nowhere, but it can make uncertain outcomes feel more immediate. When outcomes feel immediate, people discount the future more. They choose the option that resolves things now, even if it pays less later.

You can see it in a concrete situation like negotiating a car purchase. Someone hunched over a phone, shoulders forward, may feel the salesperson’s “limited time” pressure more sharply. The same person sitting back with a more open rib cage may experience the exact same message as less pressing. The words are identical. The body’s timing signal is not.

Power cues change how assertive a choice feels

Posture is also social information. Open, expansive positions are read by others as higher status, while closed, protective positions can be read as lower status or uncertainty. But the effect isn’t only external. People track their own shape and adjust behavior to match what that shape “means” in social settings. When someone feels smaller—arms tucked in, shoulders rounded—they often choose less confrontational options. They may accept terms, soften language, or avoid asking for clarification because those actions feel like they will cost more socially.

The evidence on “power posing” specifically is mixed, and findings vary by study and method. Still, the everyday part is consistent: posture changes how much social pushback someone expects. If pushback feels likely, people tend to pick safer, more defensible choices. If pushback feels unlikely, they tend to choose more direct options, even when those options aren’t objectively better.

Posture changes what you notice and remember

Decision making is constrained by attention. Head angle, eye line, and how still the body is can change what gets sampled from the environment. A forward head posture often pairs with looking down, which reduces scanning and makes the immediate object—your inbox, your notes, the price on the screen—feel like the whole situation. More upright posture tends to increase scanning and can pull in more context. That can shift a decision from “pick the first workable option” to “compare alternatives,” simply because more alternatives actually enter awareness.

There’s also a memory angle. Body state can cue certain kinds of recollection. When someone is tense and contracted, memories that match that state—past conflicts, mistakes, embarrassment—can come to mind faster. When that happens, choices become more defensive. It isn’t a conscious strategy. It’s the brain retrieving examples that fit the current bodily signal.

Small shifts can tilt group decisions

In groups, posture doesn’t just affect one person’s choices. It changes turn-taking, interruption patterns, and who gets treated as confident. In a meeting room, the person who leans back with steady shoulders may be given more space to finish a sentence, while someone curled toward the table may get cut off without anyone intending to be rude. Those micro-patterns shape which options get airtime. Options that are spoken in full tend to feel more “real” and get chosen more often.

An overlooked detail here is chair and desk height. If the table edge forces shoulders up or makes elbows hover, people fatigue faster. Fatigue narrows choices. It increases preference for familiar options and pushes teams toward “good enough” decisions earlier. The final choice can look like a rational consensus, even though it was partly driven by who could stay comfortable long enough to keep arguing.