What changes when you add a living leaf to a room

You can water a pothos in a Brooklyn apartment, set a peace lily in an office in Singapore, or keep a spider plant on a windowsill in London, and something subtle happens that isn’t about décor. The room’s air is constantly mixing with surfaces, dust, and moisture. A plant adds new wet surfaces and new chemicals. It also changes how air moves right around leaves and soil. None of this is one single “plant effect” that looks the same everywhere. It varies with the plant, the potting mix, the light, the season, and how tightly the building is sealed.

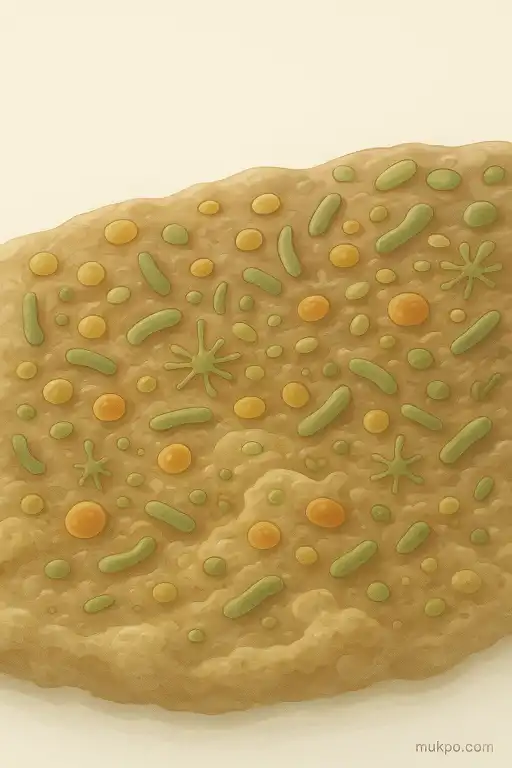

The core mechanism is simple. Plants and their soil host microbes. Plants also emit and absorb airborne molecules. Once you put them indoors, those microbes and molecules interact with an indoor environment that already has its own chemistry, shaped by cleaning products, cooking, people, and ventilation.

The plant’s microbiome isn’t just on the leaf

Indoor plants bring a whole community with them. There are microbes on leaf surfaces, but also in the root zone, in the potting mix, and on the pot itself. Those microbes can become part of the room’s microbial “background” when tiny particles or droplets move off surfaces and into dust, or when air currents lift dried fragments. Indoor dust is a major microbial reservoir, and the presence of a plant can shift what ends up in that dust over time.

One detail people usually overlook is the saucer. Water that sits under a pot can stay damp for days. That creates a stable, low-light microhabitat that is very different from a leaf. It can favor different microbes than the ones on the plant itself, and it can change what’s released into the room when the water level rises and falls or when the surface dries and flakes.

Indoor air chemistry changes because leaves “leak” molecules

Leaves release volatile organic compounds. The mix depends on species and conditions. It also changes with stress, light cycles, and temperature. Indoors, those plant-emitted VOCs don’t drift away into an open atmosphere the way they would outside. They can build up in the thin layer of air near the leaf, then mix into the room. At the same time, leaves can take up certain gases through stomata, which open and close depending on light and humidity.

Once VOCs are in indoor air, they can react. Ozone is a big player here, because it infiltrates from outdoors in many cities and can also be generated by some devices. When ozone meets VOCs, it can create new compounds and particles. Plant emissions can feed that chemistry, but plants can also remove ozone at the leaf surface. Which effect dominates depends on ventilation rates, ozone levels, and how much leaf area is actually in the room.

Soil and water are small “reactors” sitting in your living space

The potting mix is often the biggest microbial mass in the room, even if the plant looks small. Microbes in soil can transform nitrogen compounds, sulfur compounds, and carbon-based molecules, and some of those transformation products can become airborne. Moist soil also changes humidity right above the pot. That matters because water in the air affects how fast certain reactions happen and whether chemicals stick to surfaces or stay airborne.

A concrete example: a plant watered in the evening in a bedroom can leave the soil surface damp overnight, when the room is darker and cooler. Stomata behavior shifts with light, and evaporation patterns shift with temperature. The result can be a different overnight mix of VOC release, uptake, and microbial activity than you’d get in the same room with the same plant watered in the morning. It’s not dramatic in a single night, but it’s a real way “houseplant air” can be time-of-day dependent.

What you detect depends on building airflow and where you measure

Indoor air is not evenly mixed. There are small zones: a boundary layer right on a leaf, a plume of humid air rising from soil, and stagnant corners where dust settles. If someone measures microbes or chemicals near the plant, they can see a different picture than if they sample air across the room or near an HVAC return. That’s why results across studies can look inconsistent even when they are describing the same basic processes.

Ventilation also decides whether plant-driven changes linger. In a leaky older building, outdoor air can dilute plant-emitted VOCs quickly and constantly reseed indoor microbes. In a tight, energy-efficient building, indoor sources matter more, and reactions between VOCs, ozone, and indoor surfaces can run longer before being flushed out. The plant is part of that system, but the room’s airflow and surfaces often set the limits on how noticeable the change becomes.