Why bare rock doesn’t stay bare

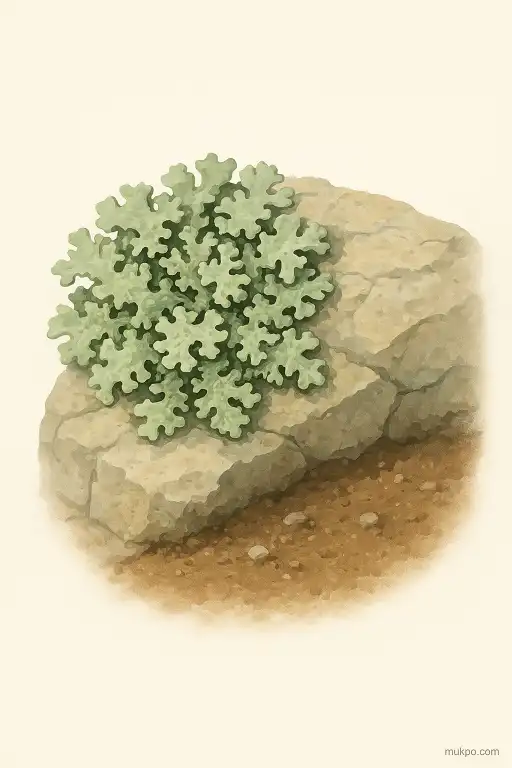

If you’ve ever walked across a fresh lava field in Iceland or looked closely at the pale granite around Yosemite, you’ve probably seen those crusty gray, green, or orange patches that look like paint splatter. There isn’t one single place where this happens. It shows up wherever rock is newly exposed, from retreating glaciers in Alaska to volcanic slopes in Hawaii. Those patches are lichens, and they’re one of the first living things that can hold on when there’s basically no soil at all. The core trick is simple: they stick tightly to rock, pull in water and dust, and slowly pry minerals loose until a thin, gritty starter layer begins to form.

What a lichen actually is, and why that matters

A lichen isn’t a single organism. It’s a partnership, usually a fungus plus a photosynthesizer (an alga or a cyanobacterium). The fungus builds the body and does most of the clinging. The photosynthesizer makes sugars when there’s light and moisture. That combo matters on bare rock because the fungus can survive long dry spells, then wake up fast when fog, dew, or rain shows up. Some lichens can start photosynthesizing within minutes of getting wet, then shut down again when they dry out.

One detail people often overlook is where the “inside” of the lichen ends and the “outside world” begins. The fungal threads can press into tiny cracks and pores in the rock surface. The contact zone is microscopic, but it’s where most of the slow work happens, because it keeps water and dissolved chemicals pinned right against minerals instead of letting them rinse away.

How lichens break rock down without teeth

Rock weathers in two main ways around lichens: physical stress and chemical attack. Physically, the lichen swells when wet and shrinks when dry. That repeated expansion and contraction puts stress on grains and along tiny fractures. It’s not dramatic day to day, but over seasons it can widen weak spots. Chemical weathering is even more important. Lichens release organic acids and other compounds that can dissolve or loosen mineral bonds at the surface. Water trapped under the lichen becomes a thin reactive film that can leach ions like calcium, potassium, or magnesium out of the rock.

Different rock types respond differently, which is why the pace varies and can be hard to generalize. Basalt, granite, and limestone don’t weather the same way. Even the same rock can behave differently depending on temperature swings, how often it gets wet, and how much dust is blowing in from elsewhere.

Where the first “soil” comes from

The earliest soil-like layer is a mix, not a single ingredient. Some of it is mineral grit scraped and dissolved from the rock. Some is windblown dust that gets caught by the rough lichen surface. And some is organic material from the lichen itself: tiny fragments, dead cells, and carbon-rich residues that stay behind. That organic fraction is small at first, but it changes what the surface can do. It helps hold moisture a bit longer. It provides carbon compounds that microbes can use.

If the photosynthesizer partner is a cyanobacterium, there’s another step that can matter: nitrogen fixation. Not every lichen can do it, and the amount varies, but when it happens it adds usable nitrogen to a place that often has almost none. That is one reason later arrivals—bacteria, free-living algae, and eventually mosses—can get a foothold in what started as plain rock.

How a thin crust turns into a living surface

Once there’s a gritty film and a little organic matter, the surface starts behaving less like rock and more like habitat. Microbes can live in the damp pockets under and around lichens. Their metabolism produces more acids and more sticky compounds that bind particles together. Freeze–thaw cycles and salt crystallization can then work on an already-weakened surface, adding new mineral fragments to the developing layer. What looks like a flat slab from standing height becomes, up close, a patchwork of micro-sites with different moisture and chemistry.

Over time—how long depends on climate and rock—mosses and small plants can start to root in the accumulating material, especially where cracks collect debris. Lichens don’t “plan” the transition, and they don’t always stick around once shade and leaf litter build up. But on open stone, especially in windy or cold places where soil is slow to form, that stubborn crust is often the first step that makes the next step possible.