Seeing a mushroom “move” is the weird part

If you’ve ever watched a little cup fungus after a rain, you might have seen something that feels wrong for a mushroom: a quick flick. There isn’t one single species that does this everywhere. Different fungi have different launch tricks. But in places like the UK and the Pacific Northwest, people often notice Peziza “cup fungi” on damp soil and wood, and bird’s nest fungi (Cyathus) on mulch. In a few groups, the cap or cup doesn’t just sit there and shed spores. It briefly changes shape, fast, to throw them.

The core idea is simple. A soft structure stores mechanical tension while it grows. Then a small, sudden collapse or snap releases that tension. The spores leave as a pulse instead of a drift.

“Collapse” usually means a fast change in pressure

Fungal tissue is basically pressurized cells packed together. The stiffness comes from turgor pressure inside those cells and from the cell walls that resist it. When a patch of tissue rapidly loses pressure, or when two regions swell and shrink out of sync, the whole cup or cap can deform in a fraction of a second. To an observer it can look like the fungus is “clapping” or buckling.

That speed matters because air has inertia. A slow squeeze just lets air flow around the spores. A fast snap pushes a little volume of air outward as a coherent puff, which can carry spores past the still air layer that hugs the surface. That thin boundary layer is a detail most people overlook, but it’s a real obstacle for microscopic particles leaving a wet surface.

Cup fungi can shoot spores with a brief “puff”

With many cup fungi (an ascomycete setup), the spores sit in long sacs called asci arranged like a lining on the inside of the cup. When they’re ready, the asci build up internal pressure and discharge. In some species the discharge is synchronized enough that you don’t just get individual pops. You get a visible spore cloud, like smoke, released in a beat.

The cup shape helps. A quick deformation of the cup rim and the coordinated firing inside can act like a tiny bellows. A person standing nearby might notice a pale haze above a brown cup on a log after it’s been disturbed, even by a footstep vibration or a raindrop. The exact trigger varies by species and conditions, and it isn’t always clear from casual observation which cue mattered most in a given moment.

Some fungi use shape changes to aim and clear the air

A “cap collapse” doesn’t always mean the fungus is literally firing like a gun barrel. Often it’s doing two quieter jobs at once: aiming and clearing. A rim that briefly buckles can redirect the airflow so spores leave upward instead of sideways into obstacles. That’s especially useful near cluttered surfaces like leaf litter, bark, or mulch where a gentle release would just stick nearby.

There’s also a timing problem. Spores are produced in huge numbers, but they only help the fungus if they actually separate from the fruiting body and get into moving air. A short mechanical event can “reset” the local air by creating turbulence right where the spores are densest. Without that, even a strong discharge can dump spores into a stagnant pocket and they can fall right back down.

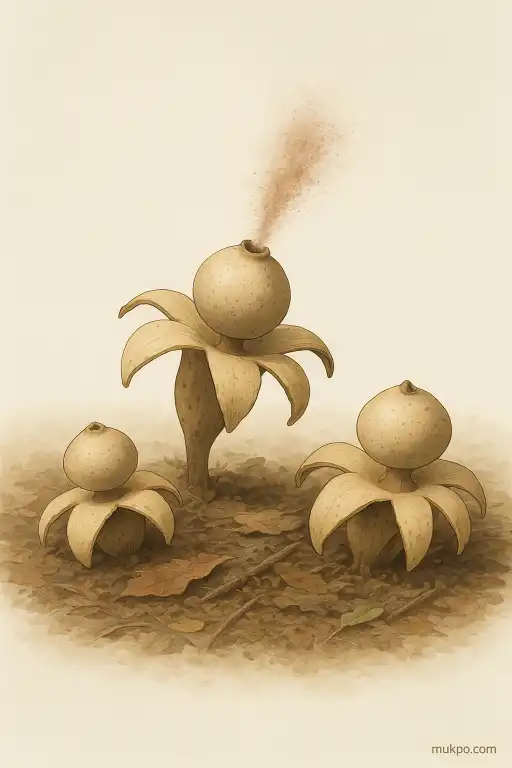

A concrete example: bird’s nest fungi fling their packets

Bird’s nest fungi are the most situationally obvious example because the projectiles are big enough to see. On garden mulch, the little cups hold several “eggs” called peridioles. A raindrop hits the cup and the cup’s shape makes the splash directional. The peridioles launch out, and a sticky cord can snag on a twig or blade of grass and wrap around it.

It’s easy to miss that the cup isn’t just a container. Its angle and stiffness matter. A slightly narrower cup can focus the splash, while a wetter, softer cup can waste the hit by deforming too much and absorbing energy. People sometimes assume any rain will do it, but the size and speed of the drop, and how waterlogged the cup already is, can change whether the “cannon” effect happens at all.