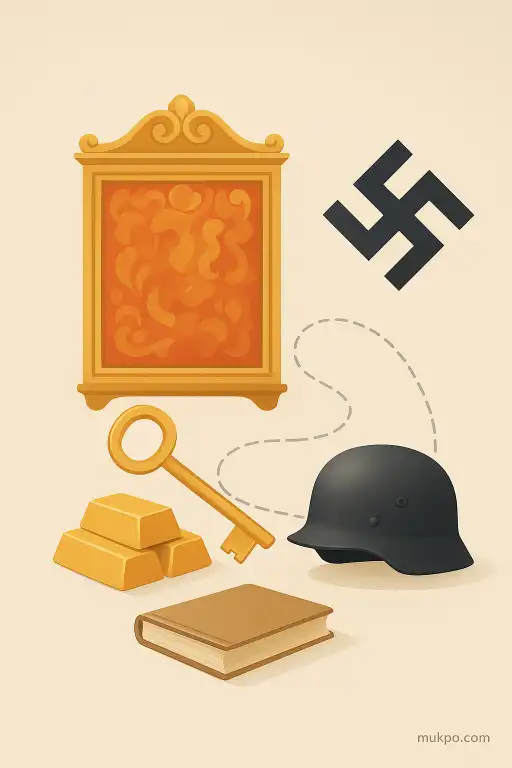

How something huge can disappear

People expect stolen art to be a painting you can roll up and slip out a door. The Amber Room doesn’t fit that mental picture. It was a whole interior—amber panels, carved decoration, mirrors—installed in the Catherine Palace near Tsarskoye Selo, outside Saint Petersburg. In 1941, during Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, it was removed fast under wartime pressure. That’s the core mechanism behind the mystery. A fragile, famous room became a set of numbered parts in crates. Once it turned into cargo, it could be rerouted, lost, burned, sunk, or hidden in ways that leave almost no clean paper trail.

What the Amber Room was, in practical terms

The Amber Room began in Prussia and was given to Peter the Great in the early 1700s. Over time it became part of Russia’s imperial display culture, refined and expanded until it felt inseparable from the palace itself. But it was never one solid object. It was a collection of panels and fittings mounted onto walls, with amber sections backed and framed, then integrated with woodwork and gilding. That construction detail matters, because “stealing the room” wasn’t like moving marble columns. It meant removing decorative elements piece by piece, packing them, and hoping they survived the trip.

A specific detail people tend to overlook is how unstable amber can be. It’s organic resin, not stone. It can crack, craze, and crumble with heat, dryness, and rough handling. Wartime transport is basically a list of those risks. Even if every crate was accounted for at the moment it left the palace, the material itself made long-term survival less certain than the legend suggests.

How it was removed and where it was taken

When German forces reached the area in 1941, Soviet curators reportedly tried to protect palace treasures, but the Amber Room was difficult to evacuate quickly. Accounts vary on the exact steps and timing, and some details remain unclear, but the result is consistent: German specialists dismantled the panels and packed them for transport. The shipment was taken to Königsberg (today Kaliningrad), where it was displayed at Königsberg Castle for a period. That part is not just rumor; it’s why the story stays anchored to a real place with records, photos, and wartime administration.

After that, the trail gets thinner. As the Eastern Front shifted and bombing intensified, artworks and archives moved repeatedly. A crate’s “last known location” often just means the last time someone bothered—or was able—to write it down. When offices are destroyed and staff are killed or displaced, documentation breaks. So the room’s disappearance is tied as much to administrative collapse as it is to any single dramatic moment.

The last sightings and the simplest ways it could be gone

Reports place the Amber Room in Königsberg into the later war years, but the final verified point is debated. Königsberg suffered heavy bombing and then brutal fighting in 1945. Any scenario from that period has problems. If it was destroyed by fire, there might be no recognizable remains, because amber doesn’t behave like metal you can recover from rubble. If it was loaded onto vehicles to evacuate, the chaos of refugee columns, military retreats, and destroyed rail lines makes it hard to trace. Even a small clerical error—one mislabeled crate, one rerouted train—can become permanent when the institutions that could correct it no longer exist.

There are also competing claims about hidden caches: cellars, mines, tunnels, or sealed rooms. Those ideas persist partly because they’re plausible in shape, not because they’re proven. Large-scale wartime storage did use underground spaces in some regions. But every additional move increases the odds of damage, theft, or abandonment, especially with a material that can be ruined by moisture, heat, or pressure.

Why the story never settles

It stays “alive” because it sits at the intersection of prestige, propaganda, and grief. For Nazi Germany, it was a trophy tied to a narrative of cultural possession. For the Soviet Union and later Russia, it became a symbol of loss that fit the scale of the war. That makes the incentives uneven. People overstate leads. Witness memories conflict. Private hoard claims appear just often enough to keep hope going, but rarely come with verifiable artifacts or chain-of-custody details that hold up.

The practical complication is that even a real surviving fragment would be hard to authenticate cleanly. Amber can be repaired, replaced, and reassembled in ways that blur “original” versus “restored,” especially after decades. That’s why the reconstruction installed in the Catherine Palace in 2003 can exist as a tangible room people can walk through, while the wartime original can still be absent in a way that never produces a single, satisfying final answer.