A question people rarely ask

How did thousands of people in 1835 end up believing the moon had bustling ecosystems? A lot of it came down to one ordinary habit: trusting what looks like a straight news report. In August 1835, The Sun in New York City printed a run of articles claiming that the British astronomer Sir John Herschel, working at the Cape of Good Hope, had made astonishing lunar discoveries. The pieces were written in the calm, explanatory voice readers expected from science coverage. They didn’t ask for belief. They performed it.

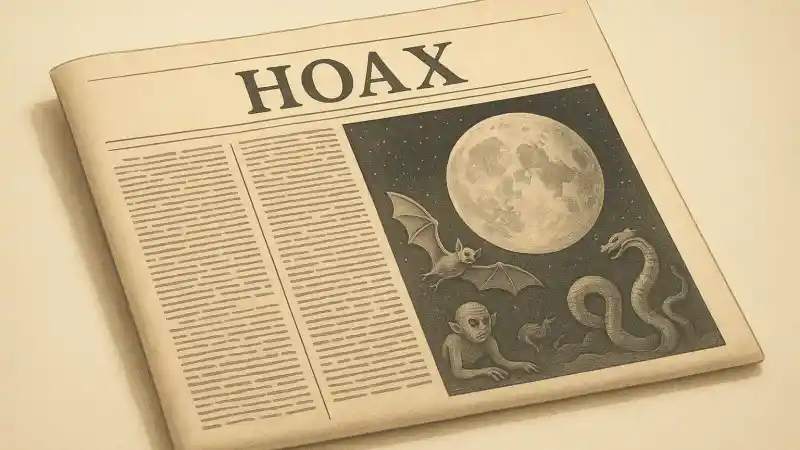

What the paper actually printed

The articles described a new, powerful telescope and a method for viewing the moon in extraordinary detail. Then came the payload: forests, oceans, and creatures that sounded both familiar and just odd enough to be “new.” The most famous were bat-like humanoids later nicknamed “man-bats,” presented as part of a larger catalog of lunar life. The writing leaned on measurements, careful scene-setting, and the tone of an eyewitness report, even though no one at the paper had seen anything.

A detail people overlook is how the story borrowed credibility from real, checkable facts. Herschel was a respected figure. He really was doing serious observing work in South Africa around that time. That mattered because readers could connect the claims to a person they’d already heard of, instead of a vague “European scientist.” The hoax didn’t need readers to know astronomy. It only needed them to recognize a name.

Why it felt plausible in 1835

Early 19th-century astronomy had a public-relations problem and an advantage at the same time. It was hard for most people to verify anything beyond what their eyes could see, but it was also a period when big scientific announcements felt frequent and disruptive. New instruments did change what could be observed, sometimes suddenly. So a claim that a breakthrough lens had revealed new lunar detail didn’t sound like magic. It sounded like progress.

There was also the simple fact of how newspapers competed. The Sun was a penny paper, built for high circulation. Sensation sold, and “science sensation” sold especially well because it carried the respectability of learning. The articles read like something that could be reprinted and repeated without embarrassment. People could pass it along as “did you see this report?” rather than “listen to this wild rumor.”

The mechanics of credibility

The hoax worked because it stacked small signals that readers had been trained to treat as proof. It used a serialized format, which mimicked the way real dispatches arrived over time. It name-dropped institutions and publications in a way that sounded like sourcing, even when the references didn’t resolve cleanly. And it offered specific-seeming technical detail about optics and observation, which is hard to evaluate quickly but easy to mistake for expertise.

It also leaned on a psychological trick that isn’t dramatic but is powerful: once a person accepts the first premise (Herschel observed something new), the later premises (the moon has animals; one looks vaguely human) ride along with less resistance. Each new installment didn’t have to win belief from scratch. It only had to feel consistent with what had already been printed yesterday.

How it unraveled, and what lingered

As the story spread, it ran into the limits of verification. Astronomers and more technically minded readers asked where the original report had appeared and how the described instrument could do what it claimed. Some of the cited publication trail didn’t hold up. At some point the series was widely recognized as a fabrication, and it became known as the “Great Moon Hoax.” Exactly how quickly disbelief overtook belief varied by audience and by access to skeptical commentary.

What stuck wasn’t just the image of creatures on the moon. It was the template: a real scientist’s name, a plausible setting, confident technical language, and a delivery system that made the claims feel like yesterday’s news becoming today’s accepted fact. Even after the joke curdled, the articles were still entertaining to read, which meant they kept circulating as a story about how easily a serious tone can borrow authority.