What people mean by “plastic-eating bacteria”

People rarely ask what “chewing plastic” would even look like in the open ocean. It’s not a single discovery in one spot. Reports tend to come from several ocean regions where plastic concentrates, like the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (often linked with the Great Pacific Garbage Patch), the North Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean. The basic idea is simple, though. Microbes settle on the surface of drifting plastic. They form a slimy layer. Some of them can use parts of the plastic, or the chemicals leaking from it, as food.

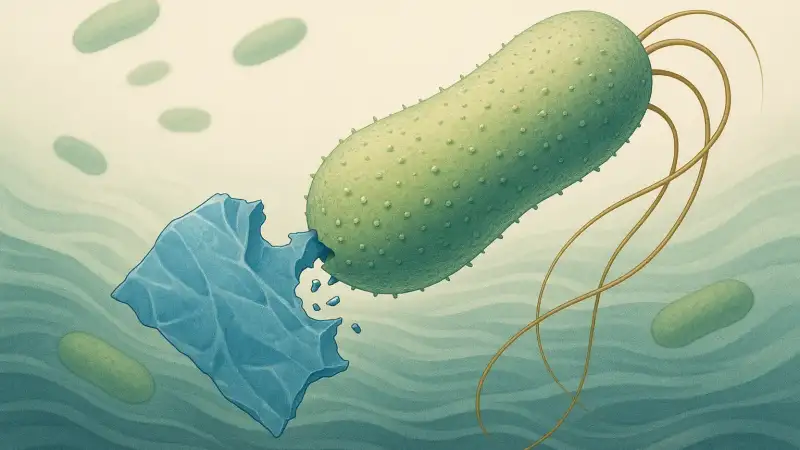

The core mechanism usually isn’t a bacterium biting a bottle into crumbs. It’s chemistry at the surface. Enzymes and oxidation slowly change the polymer chains. Then smaller fragments and additives become easier for microbes to take up. A detail people overlook is that most of the action happens on the outer micrometers of the plastic, where sunlight, salt, and abrasion have already weakened the material.

Gyres are not trash islands, and that matters

Ocean gyres are huge rotating current systems, not floating landfills you can walk on. Plastic gets trapped because the circulation keeps pulling buoyant debris toward broad, slow-moving centers. The debris is spread out, often as small pieces and fibers. That changes what microbes can do. A bottle cap drifting for years becomes brittle. It develops cracks and pits. Those tiny surface defects become shelter and attachment points for cells.

Conditions in a gyre also make plastic surfaces unusually “busy.” Sunlight can pre-oxidize polymers. Waves and sand-sized particles scuff them. Temperature and nutrient levels vary by season and depth. So when scientists find bacteria associated with plastic in one cruise, it doesn’t always match what another team finds later. Even within the North Pacific Gyre, communities can differ between a sunlit surface sample and a sample taken a few meters down.

The plastisphere: a thin living skin on plastic

Researchers often describe a “plastisphere,” meaning the biofilm community that grows on plastic in water. It’s not just bacteria. It can include algae, fungi, and small grazers, depending on the location and the age of the fragment. The biofilm changes the plastic’s behavior. It can make a piece heavier and more likely to sink. It can also change how the surface interacts with pollutants, because sticky biofilms trap organic compounds and metals.

Not every organism on plastic is breaking it down. Many are simply using it as a raft. Some are eating other microbes. Some are taking advantage of additives bleeding out of the material. A common confusion is to treat “living on plastic” as proof of “eating plastic.” In lab studies, a microbe might appear to reduce plastic mass, but it may actually be consuming residue, plasticizers, or weathered byproducts rather than the tough polymer backbone itself.

What “degradation” usually means in real ocean conditions

When a bacterium is said to degrade plastic, the important question is what kind of plastic and what end point. PET (used in many bottles) has known enzymes in some microbes under certain conditions, but PET is only one material. Polyethylene and polypropylene, which dominate floating debris, are chemically stubborn. In the ocean, they mainly fragment first from UV exposure and physical wear. Microbial activity, when it happens, often targets the oxidized, already-damaged parts.

Another overlooked detail is oxygen and nutrient availability on a drifting fragment. The outer biofilm can have oxygen from seawater, while tiny pockets deeper in the film can become low-oxygen. Different metabolisms can coexist on the same speck of plastic. That can speed up the consumption of certain breakdown products. It still doesn’t guarantee the original polymer disappears on human timescales. Often, the measurable change is subtle: shifts in surface chemistry, tiny mass loss, or increased brittleness rather than clean “digestion.”

Why scientists keep searching, and why the story stays messy

Scientists keep hunting for plastic-degrading microbes in gyres because the setting is a long-running natural experiment. Plastic stays in the system for years. Surfaces are constantly being colonized. If a microbe can survive by using polymer fragments or related compounds, gyres are where it would have repeated chances. But the evidence comes in layers: microscopy showing pitted surfaces, genetic hints of enzyme families, lab incubations with plastic as a carbon source, and chemical measurements of byproducts. Those layers don’t always line up cleanly.

There’s also a scale problem. A bacterium that breaks down a thin film in a warm lab flask may behave very differently on a cold, nutrient-poor fragment drifting through the North Pacific. And the “success” case may be a community, not a single species acting alone. That’s why reports often read like partial answers: promising enzymes here, slow surface changes there, and a growing catalog of microbes that clearly thrive on the plastic lifestyle even when true polymer digestion is still hard to prove.