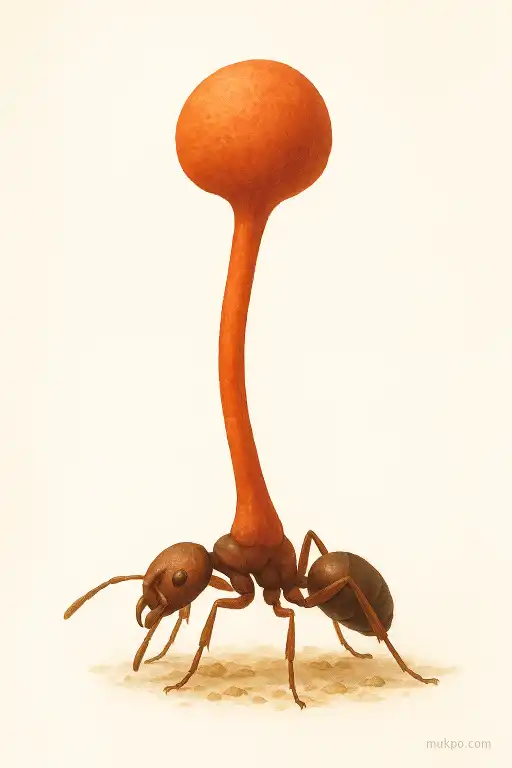

If you watch a line of ants crossing a forest floor, it looks like pure teamwork. But sometimes that “team” includes a fungus that steers the job from the inside. This isn’t one single event in one place. Versions of it have been documented in Brazil, Thailand, and the southeastern United States, often involving fungi in the Ophiocordyceps group and different ant species. The core mechanism is unsettlingly practical: spores get into an ant, the fungus grows through its body, and the ant starts following new instructions. Those instructions include where to walk, where to stop, and what to do with its mouthparts.

The moment the ant stops acting like an ant

After infection, the ant usually keeps doing normal ant things for a while. Then its behavior shifts in ways that don’t help the colony. It may leave the nest at an odd time, wander without clear purpose, and climb vegetation instead of staying on the ground or returning to trails. Researchers often describe a final, abrupt change where the ant settles into a specific spot and won’t be “talked out of it” by normal ant cues. That’s the point where the parasite’s goals start to look more important than the ant’s.

A concrete example that shows up in field reports is an infected ant ending up on the underside of a leaf or along a vein. That choice is not random. The underside can reduce exposure to rain and sunlight, and the leaf surface can hold a steadier temperature and humidity than open ground. Those microclimate differences are easy to overlook because they’re measured in centimeters, not landscapes.

How the fungus gets a trail built for it

Ant trails are made from repeated trips plus chemical marking. Some infected ants still move in ways that lay down a path. They walk, pause, turn, and walk again, often along edges and stems where other ants already travel. If an infected ant is shedding spores or fungal fragments as it moves, those surfaces become a delivery route. Other ants don’t need to be “tricked” into following it. They just keep using the same convenient corridor, and the corridor becomes a contact zone.

When the infected ant finally clamps down with its jaws, it can stay put long enough for the fungus to mature. In well-known “lockjaw” cases, the grip is so strong that even after death the ant remains attached. That fixed position can place the fungus directly above or beside active traffic. If spores drop or get brushed off, a busy trail makes a big difference.

What the fungus is doing inside the body

Inside the ant, the fungus doesn’t just sit in the gut. It grows as a network through the body cavity and into tissues. In several Ophiocordyceps–ant systems, studies have found dense fungal growth around muscles, especially in the head and legs, while the brain can be less directly invaded than people assume. That detail gets missed because “mind control” sounds like a brain story. In these ants, it may be more of a body story: change the muscles and the signals they receive, and you can change the movement.

The fungus also releases chemicals that interact with the ant’s biology. Which compounds matter most seems to vary by species, and it’s still unclear how universal any single pathway is. But the general pattern is consistent: the ant’s normal routines break, its movement becomes more predictable, and its final position lines up with what the fungus needs for growth and spore spread.

Why “the perfect leaf” matters so much

The fungus needs time to build a spore-producing structure after the ant dies. That structure is sensitive to drying out. So the ant’s last climb often puts it in a spot with higher humidity and fewer temperature swings, like shaded understory leaves. In some places, clusters of dead ants can appear at similar heights on plants, because that height matches local conditions. It looks eerie, but it can be explained by the fungus repeatedly selecting the same stable zone.

One overlooked detail is timing. Some infected ants change their behavior at particular times of day, which can align with daily humidity cycles and the ant colony’s traffic patterns. If the goal is to land near routes other ants will use, when you arrive can matter almost as much as where you arrive.

Why colonies don’t just collapse

It’s tempting to imagine a whole colony turning into fungus-driven robots. That usually isn’t what’s observed. Ant colonies have defenses: grooming, removing sick individuals, and avoiding contaminated areas. Some species change their foraging routes, and some will physically remove dead bodies from near the nest. Those behaviors can limit how many workers get exposed, even when the fungus is present in the environment.

At the same time, the fungus doesn’t need to infect everyone. It just needs a steady trickle of hosts, placed in the right spots, often close to where ants already move. A few manipulated workers can be enough to keep the cycle going in a forest where trails are constantly being made, erased, and made again.