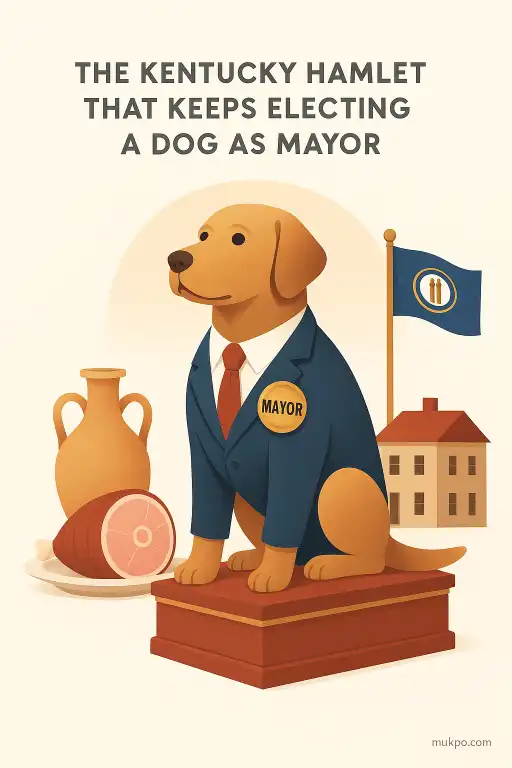

A mayoral race where the candidate wags instead of waves

It’s a little jarring the first time you hear it: a Kentucky hamlet that keeps electing a dog as mayor. The place most often tied to this kind of story is Rabbit Hash, just across the river from Cincinnati, which has repeatedly “elected” dogs in a fundraiser-style vote. The core mechanism is simple. People pay to cast ballots, the proceeds support local needs, and the winner gets the title. It looks like a civic prank from far away. Up close, it tends to be a small community’s way of keeping attention—and money—flowing toward a place that doesn’t have many levers to pull.

Rabbit Hash is tiny, and that’s part of the point

Rabbit Hash is unincorporated, which is the detail people usually overlook. It is not a city with a formal municipal government in the way most people imagine when they hear “mayor.” That matters because the dog isn’t signing ordinances, hiring staff, or controlling a budget. The title is honorary, and the “election” isn’t a government-run, legally binding contest. It’s a community event that borrows the familiar ritual of voting because it’s instantly understandable, even to people who have never been to Boone County.

The hamlet’s fame also tends to hinge on a specific local anchor: the Rabbit Hash General Store. When people talk about the dog mayor, they’re often talking about the store as much as the animal. In small places, a single building can function like a town square. If that place needs repairs, draws visitors, or is trying to stay open, a quirky election becomes a practical tool dressed up as a joke.

How the dog elections usually work

These races are typically run as fundraisers with a voting window, candidates, and some rules about eligibility. The exact details can vary by year, and they are set by the organizers rather than by a county clerk. Voting is often tied directly to donations: one dollar equals one vote, or something close to that. The “campaigning” is mostly photos, short bios, and people lobbying friends online. The dog’s owner does the human parts, like showing up for events and handling any scheduling.

There’s also usually a loose job description, because people want the bit to feel real. The dog mayor might “attend” a parade, “welcome” visitors, or appear at a charity day. The best candidates are the ones with a patient temperament. They can tolerate strangers, noise, and being gently fussed over. That’s a more limiting requirement than it sounds, and it’s one reason the same small network of local pet owners often ends up involved again and again.

Why people keep doing it instead of moving on

If the whole thing were only about being silly, it would probably burn out. The staying power comes from a mix of identity and economics. A tiny place that doesn’t have a lot of industry can still have a story people want to repeat. A dog mayor story travels well because it’s easy to tell in one sentence, and it gives outsiders a reason to stop by, buy something, take a photo, and donate. That attention can be worth more than any single election cycle’s proceeds.

It also gives locals a safe way to participate in “politics” without fighting. In a real municipal election, the stakes can be high and personal. In a dog election, people get the pleasure of choosing sides without the usual resentment. The “campaign issue” becomes whose pet is friendliest, whose owner is most involved, or which story best fits the place’s image. The ritual scratches the same itch as civic life—without the collision.

The part outsiders misunderstand when they hear “mayor”

Most confusion comes from a category error. When a headline says “dog elected mayor,” readers picture an official government role being handed to an animal. In Rabbit Hash, the title is more like “mascot with duties.” The county still has its normal structure. Roads, policing, and zoning aren’t being run out of a doghouse. The dog’s job is symbolic, and symbolism is exactly what small communities trade in when they don’t have big resources.

That symbolism can still have real consequences. A known “mayor” makes fundraising easier, because it gives donors a story to attach to their money. It can pull media coverage toward a place that would otherwise be skipped. And it can keep a community landmark—often the overlooked part of the story—on people’s mental map. The election looks like a gag. The maintenance, insurance, repairs, and volunteer hours behind it are not.