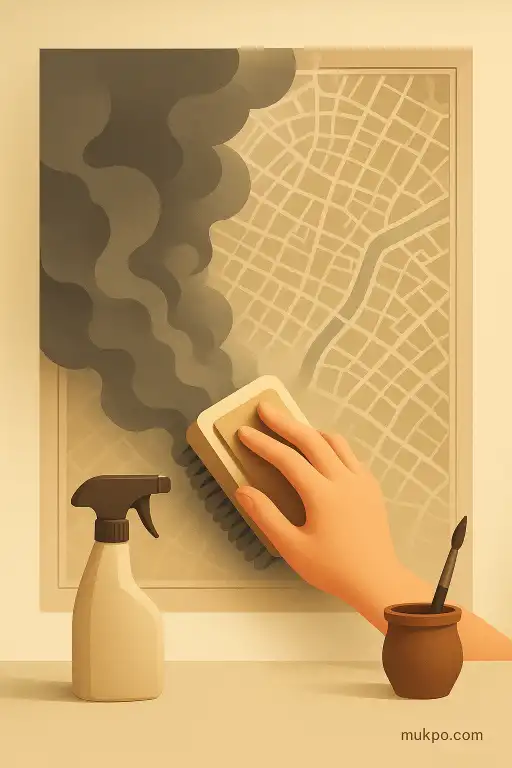

Smoke does a funny thing to murals. It doesn’t just make them look “dirty.” It can lay down a thin, stubborn film that flattens every color into the same tired brown. When conservators start cleaning, the change can feel almost unreal. A pale patch turns bright. A shadow becomes a line. And sometimes a line becomes information. That’s how a few restorations have surprised people, including the famous conservation work in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, where removing grime changed what viewers thought they knew about the paint. Not every project is that dramatic, and the “hidden map” story isn’t tied to one single confirmed mural, but the mechanism is real: smoke deposits come off unevenly, and the underpainting comes back in pieces.

Why smoke can hide more than color

Most of the darkening comes from soot and oily residues that drift through air and stick to surfaces. In older buildings, that might be fireplace smoke, candle soot, cooking fumes, or tobacco. The deposits don’t settle like a uniform blanket. They cling more to rough paint passages than smooth ones, and they build up fastest where air currents repeatedly pass. Corners, ledges, and the upper parts of walls often look worse, not because the artist painted them darker, but because warm air rises and carries particles with it.

One detail people tend to overlook is that soot can create a false sense of “age” by muting contrast. It hides fine lines first. Thin outlines, hatching, and lightly glazed color shifts disappear before bold shapes do. So if an artist embedded a city plan using faint ink-like lines or pale washes, that information is exactly what smoke will erase from view first.

How a map can be there without anyone noticing

Murals often have more than one kind of drawing inside them. There’s the visible design, but there can also be underdrawing and revisions. Artists sometimes transferred layouts using charcoal, red chalk, or incised lines. Some did it freehand. Some used cartoons. A “map” might not be a literal street grid painted for viewers. It could be a planning scaffold that later got painted over, or a background detail that was meant to be subtle, like rooftops arranged to match a real neighborhood.

Another way a map-like image shows up is through pentimenti, the traces of changes. If a muralist initially sketched a panorama with accurate blocks and roads, then simplified it later, the earlier structure can still sit underneath. It stays invisible until the surface layer is altered by grime, varnish discoloration, or cleaning that restores separation between tones. The “reveal” feels like discovery, but it’s usually the return of contrast rather than the uncovering of a separate secret layer.

What cleaning actually removes (and what it shouldn’t)

Cleaning a mural isn’t like wiping a window. Conservators test tiny areas first, because the dark layer might be dirt, but it might also be original glaze, aged varnish, or later overpaint. Smoke residues are often a mix: carbon particles plus sticky compounds that can migrate into porous paint. That’s why cleaning can proceed millimeter by millimeter. A solvent or gel might lift grime from one pigment safely and disturb another. Even water can be risky on certain binders.

That slow pace is part of why “a map emerges” tends to happen gradually. A cleaned patch doesn’t just look brighter. It restores edges. It clarifies intersections. When enough neighboring passages are cleaned, lines that seemed decorative can suddenly connect into something readable, like a shoreline, a wall line, or a road. Photographs taken in raking light can make this more obvious, because shallow surface texture changes—cracks, incisions, raised brushwork—start to read again as intentional marks instead of random noise.

Why people read a city into the revealed lines

Once the eye catches a pattern that looks like a street plan, it keeps looking for confirmations. That’s not foolish. It’s how we recognize real maps, too: repeated angles, consistent widths, junctions that behave like intersections. Murals that depict civic pride—ports, markets, churches, fortifications—are especially prone to this, because they already contain architecture and infrastructure. When smoke has blurred the scene, it can reduce buildings to blocks. Cleaning puts back the distinctions that make those blocks feel like districts.

But there’s also a genuine art-historical reason a city layout might be present. In parts of Europe, detailed vedute and city panoramas became popular long before modern street maps were common household objects. In some contexts, a mural’s background could function as a readable reference for locals. If the building served a civic role, the mural might have been intended to be “accurate enough” to recognize a gate, a river bend, or a main route, even if it wasn’t labeled like a paper map.

How experts decide whether it’s a real map or a lucky pattern

A cleaned image that resembles a map still has to be checked against other evidence. Conservators and historians compare the lines to known plans, prints, or historical descriptions, when those exist. They also look for internal consistency: does the scale shift in a believable way, or does it collapse into decoration? Technical imaging helps too. Infrared reflectography can reveal underdrawing. X-radiography can show changes in dense pigments. Those methods can indicate whether the map-like structure was planned from the start or emerged from later repainting.

Sometimes the answer stays unresolved. A mural might hint at a specific city without enough surviving detail to match it to one plan. Smoke damage can erase the very labels or landmarks that would settle the question. So the “hidden city map” may end up as a working interpretation rather than a solved fact, sitting in the space between what the cleaned wall shows and what the building’s history can still prove.