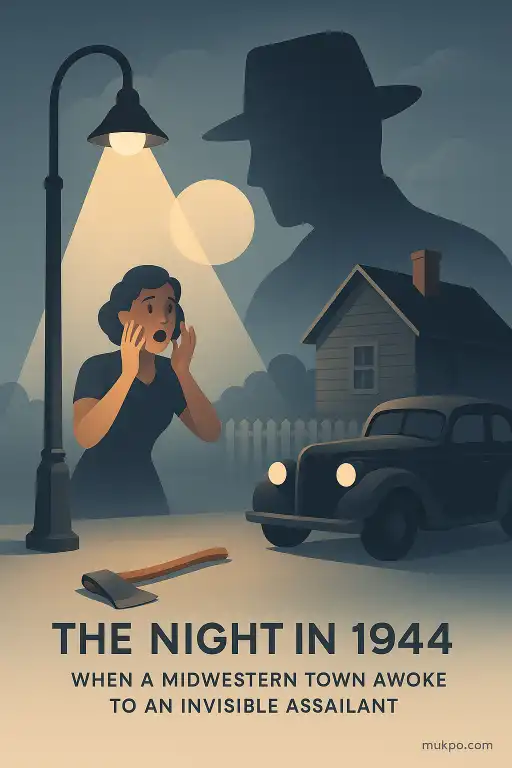

People like to believe you can always tell when you’re under attack. In Mattoon, Illinois, in 1944, that certainty didn’t hold. Residents reported waking up with a sickly sweet odor in their rooms, then feeling dizzy, nauseated, or suddenly weak. Some said their lips and throats burned. Others described partial paralysis that faded after a while. They searched for footprints, broken locks, and obvious intruders, but nothing lined up. The story that spread was simple: someone was slipping through windows and screens, spraying a chemical, and vanishing into the dark.

What people in Mattoon said happened

The reports clustered in late August and early September 1944, and the details often sounded domestic: a bedroom window left slightly open, a screen that didn’t fit tightly, a couple awakened from sleep. A common thread was the smell. Witnesses compared it to perfume, ether, or “sweet” fumes, and the symptoms followed fast—headache, nausea, tightness in the chest, trembling. Some people described numbness in their arms or legs and an inability to move for a short time. The effects usually wore off, which made the episodes easier to dismiss and harder to pin down.

One overlooked detail is how much the accounts depended on waking up already frightened and already scanning for an explanation. A noise outside, a shadow by a window, or the sense of a presence could snap into focus after the smell hit. In more than one account, the “spray” itself wasn’t seen at all. The idea of it arrived later, when people tried to turn a set of sensations into a mechanism that made sense.

Why “invisible” felt plausible in 1944

Mattoon’s panic didn’t happen in a vacuum. It was wartime America. People were primed to think about sabotage, chemicals, and hidden threats, and newspapers were full of stories about new weapons and industrial hazards. A prowler who left no marks but caused real physical distress fit that mental template. Even the term that later stuck—“Mad Gasser”—shows how quickly a label can harden into a character, especially when it gives a town a single thing to look for.

It also mattered that the setting was ordinary. These were not sealed labs or guarded depots. They were porches, alleys, open windows, and screens that had been repaired a few times. A small gap in a screen can feel trivial until a rumor tells you it’s a doorway. Once that idea is in the air, any nighttime odor—cleaning fluid, paint, engine exhaust—starts to feel like evidence.

How the body can supply symptoms without a clear toxin

If a person believes they’ve inhaled something dangerous, the body can do a lot on its own. Hyperventilation and panic can produce tingling, numbness, chest tightness, dizziness, and weakness. Waking suddenly from sleep makes it more intense. So does trying to stay quiet so you can “hear the attacker,” which can lock someone into shallow breathing. Those symptoms are real. They’re just not always tied to an external chemical dose.

The smell reports complicate things, because odor does imply something in the air. But odors travel oddly at night. A light breeze can push fumes from a garage, a refinery-related source, or a nearby vehicle right into a bedroom window, then vanish minutes later. People often overlook how strongly smell anchors memory. Once a scent is associated with fear, it becomes easier to notice and harder to ignore, even at low levels.

Why the evidence stayed slippery

An “invisible assailant” is hard to catch because the normal proof doesn’t accumulate. There were no consistent footprints, no clear pattern of entry, and no recovered device that everyone could agree on. Reports varied on where the attacker stood, how the spray was delivered, and what the odor resembled. That variation matters. It suggests the town was reacting to a cluster of experiences rather than a single repeatable method.

There’s also the timing problem. Most incidents were reported after the fact, when symptoms had already peaked or started to fade. That’s exactly the window when people rush to open doors and windows, turn on fans, or move from room to room. Those actions change the air quickly and can erase the very trace someone would need to test. In 1944, routine home air sampling wasn’t sitting on a shelf, ready to deploy.

What keeps a night like that alive in local memory

Once a town is watching for a specific kind of threat, attention becomes contagious. A neighbor’s story makes you listen harder for sounds in the alley. A newspaper headline makes a harmless odor feel targeted. The events in Mattoon weren’t just a set of complaints; they became shared material, discussed on porches and in workplaces. That’s how an attacker can feel “everywhere” even when no one can point to a single, verifiable presence.

And because the symptoms were frightening but usually temporary, people could return to daily life while still believing the danger was active. That combination—real discomfort, an unclear source, and a story that fits the moment—creates a kind of vigilance that can last for weeks. It doesn’t require a captured culprit to stay vivid. It only requires one more night where someone wakes up, catches a strange smell, and can’t fully explain what their own body is doing.