A well that “turns things to stone” isn’t just one place

People lose small things all the time. A plastic toy in a pocket. A key fob in a bag. Then they hear there’s a well where objects come back looking like stone, as if the water did something impossible. It isn’t one single well with one fixed story. The most concrete, named examples are “petrifying” waters in places like Knaresborough in North Yorkshire (often tied to the Mother Shipton legend) and the Petrifying Well at Dunnottar near Stonehaven in Scotland (accounts vary on the exact site and naming). Similar effects also show up at mineral springs used for “petrifying” displays in several countries. The mechanism is not magic, but fast mineral coating.

What the water is doing, step by step

The water isn’t turning the toy’s material into rock. It’s building a rock-like shell on the outside. At many of these sites, water flowing over limestone picks up calcium carbonate. When it reaches open air again, it loses carbon dioxide and the dissolved mineral can precipitate out as calcite. That calcite sticks to surfaces. If the flow is steady and the chemistry is right, the coating can build up quickly enough to look dramatic within weeks or months.

This is the same basic chemistry behind stalactites and stalagmites. The difference is scale and exposure. In a well, dripping wall, or trough, objects can sit right in a thin sheet of mineral-rich water. They get coated everywhere the water touches, especially along edges and seams where droplets linger.

How “lost toys” end up looking petrified

In the tourist versions, objects are usually hung or placed where water is actively depositing minerals. At Knaresborough, for example, souvenirs and everyday items have historically been displayed under the flowing water so visitors can see them become crusted over. A small toy left in the wrong spot can go through the same treatment. It comes back heavier, duller, and gritty. Details soften as the coating thickens, so it can read as “stone” even though the original plastic is still inside.

The effect depends on surface texture. A fuzzy toy, a keychain with fabric, or something with lots of pores gives crystals many places to start. Smooth plastic can coat too, but it tends to begin at scratches, logos, and molding lines. That’s why two identical toys can “petrify” at different rates if one has a scuff or a bit of sticky residue on it.

The overlooked detail: air matters as much as water

People focus on the water chemistry, but airflow and splashing can matter just as much. Calcium carbonate often precipitates as carbon dioxide escapes from the water. That happens faster when the water is thinly spread, agitated, or broken into droplets. A toy sitting fully submerged may change less than a toy that’s constantly being dripped on. The “petrifying” spots are usually the ones where water is moving from a confined channel into open air.

Temperature swings can also shift how readily minerals come out of solution, and so can biological films. Algae and bacteria on rock surfaces can trap particles and provide nucleation sites for crystals. That slimy layer is easy to miss, but it can speed up the start of a coating, especially in shallow wells where light reaches the water.

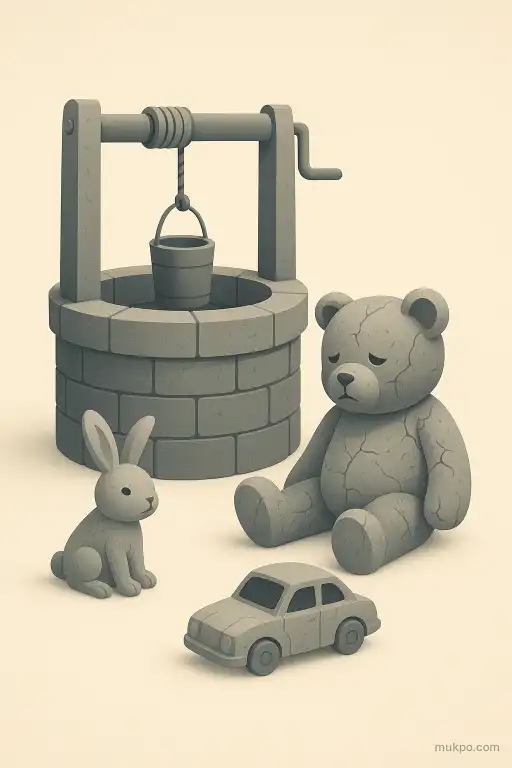

Why it feels uncanny even when you know the chemistry

A coated toy creates a specific kind of confusion. It keeps its shape, like a cast, but the surface changes completely. The weight jumps. The sound changes when it’s tapped. Edges that were soft become hard. If the coating is thick, it can even bridge gaps and “freeze” moving parts, like a hinged limb or a spinning wheel. That’s part of why these wells gather stories about lost objects coming back transformed.

And the timing is hard to judge by eye. Some sites produce a visible crust quickly, while a truly chunky, stone-like shell can take much longer and may never happen evenly. That variability makes the phenomenon feel personal and unpredictable, especially when the object is something small and familiar, like a child’s toy.