The pause before sound

There isn’t one single “speak up” moment. It happens in a meeting at Google, at a city council microphone in Chicago, or at a family dinner where someone says something off. The seconds before a person talks are usually busy, even if they look still. The brain is already treating speech as a physical act that might have consequences. It’s weighing social risk, picking words, and preparing muscles. Some of this is conscious. A lot of it is not. That mix is why the pause can feel oddly loud inside the body.

The threat check happens fast

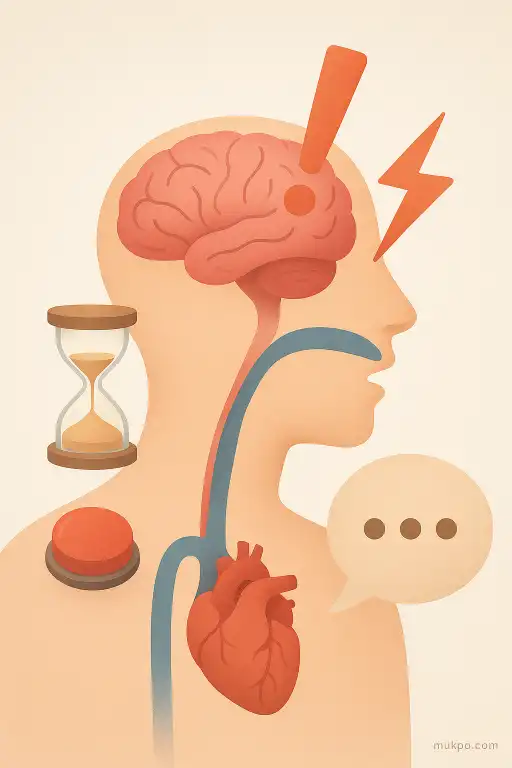

Before the first word, the brain does a quick “how safe is this?” scan. It pulls in facial expressions, tone, status differences, and whether the room feels friendly or tense. If the moment reads as risky, the amygdala and connected circuits can push the body toward a stress response. That doesn’t require panic. It can be subtle. A small spike in arousal is enough to change what comes next.

That shift shows up as physiology. Heart rate can jump. Breathing can get shallower. Blood flow tends to favor large muscles over fine control. Stress hormones like adrenaline can rise quickly, while cortisol tends to lag behind. The result is that speaking starts to feel like a bigger act than it “should,” even when the content is ordinary.

Your lungs and larynx get involved before your mouth does

Speech rides on breath, so the respiratory system often moves first. A person may take a preparatory inhale without noticing. The timing matters because speaking usually happens on an exhale, with controlled airflow. If someone is holding their breath from tension, they may feel “stuck” right before talking because the system has to reset: inhale, then release air steadily enough to power sound.

The larynx is part of this setup. Tiny muscles adjust the vocal folds so they can vibrate cleanly. Under stress, those muscles can tighten. That changes pitch and makes the voice sound thinner or higher. A specific detail people overlook is swallowing. Right before speaking, many people swallow once. It’s a quick way to clear saliva and reposition the larynx, but it can also be a sign of dry mouth as the sympathetic nervous system reduces salivation.

Word choice competes with self-monitoring

In the same seconds, the brain is building the sentence. That involves selecting meaning, retrieving words, and arranging them into grammar, while also planning the motor sequence to produce them. At the same time, there’s monitoring. It checks how the words might land, whether they violate group norms, and whether they match the image a person is trying to maintain. That self-monitoring tends to increase when the stakes feel social rather than factual.

That competition can create the familiar feeling of having the thought but not the words. It’s not that the idea vanishes. It’s that retrieval slows when attention is pulled toward evaluation. In a concrete situation like a team meeting, someone may be tracking the manager’s expression, the last person who spoke, and the room’s silence all at once. The brain is doing that while trying to pick between near-synonyms, because each one implies a different level of certainty, blame, or softness.

The first syllable is a motor event

When speech finally starts, it’s a coordinated movement pattern. The tongue, lips, jaw, and soft palate have to hit precise targets in tens of milliseconds. The cerebellum and motor cortex help run that timing, and the auditory system listens immediately for errors. That feedback loop is so fast that people can adjust volume and pitch mid-word without deciding to. It’s also why a shaky start can settle after a couple of syllables, once the system locks onto a stable rhythm.

If the body is in a heightened state, the motor system can overshoot. The voice may come out louder than intended, or the first consonant may “catch.” Sometimes there’s a brief vocal fry or a breathy onset because airflow and vocal fold closure didn’t line up perfectly. None of that requires a big emotion. It can happen from a small, quick stress response paired with the simple fact that speaking is one of the most precise things the body does in public.