A drain that “looks clean” can still be alive

If you pull the stopper in a bathroom sink, you sometimes see a dark ring where water sits. It shows up in apartment kitchens in New York, in older homes in the UK, and in high-rise bathrooms in Singapore. It isn’t one single place or one famous incident. It’s a process that happens wherever water, soap, skin oils, and time meet. That ring is usually a biofilm: microbes stuck to a surface, held together by a slimy matrix they make. The core mechanism is simple. Flow brings food and cells. Surfaces give them a place to attach. Then the community builds a protective layer that changes what “clean” even means in that spot.

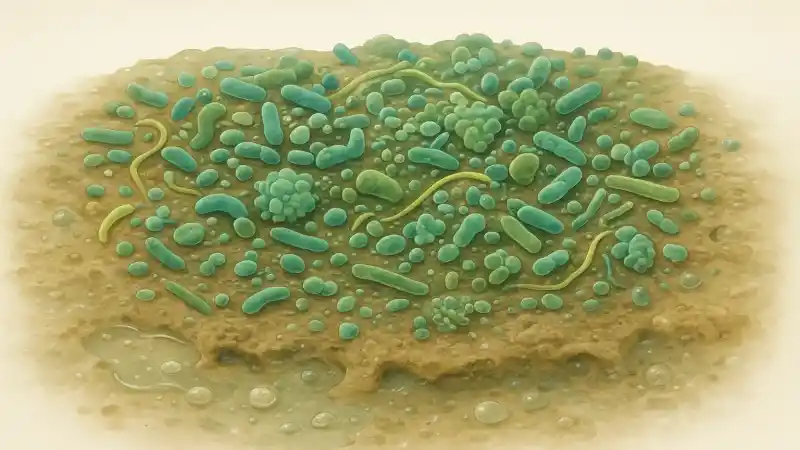

Biofilm is a structure, not just gunk

A biofilm is not just a pile of organisms. It’s an organized patchwork. Bacteria and fungi attach first, then secrete extracellular polymeric substances, a mix of sugars, proteins, and DNA that acts like glue. Inside that matrix, oxygen and nutrients don’t spread evenly. The outer surface can be oxygen-rich, while deeper layers are low-oxygen or even oxygen-free. That gradient matters because it lets different species live inches apart in the same drain and still prefer different conditions.

One detail people often overlook is how much of the biofilm can sit above the waterline. The slick area just under the drain flange or along the overflow channel can stay damp without being submerged. That thin, intermittently wet zone gets frequent exposure to air and fresh inputs from handwashing. It can support a different mix of microbes than the fully submerged section of a trap.

What tends to live there depends on what the drain “eats”

Household drains are fed by routines. Bathroom sinks get skin cells, toothpaste residue, and soap surfactants. Kitchen sinks get fats, starches, proteins, and occasional bursts of hot water. Those inputs select for different microbes. Skin-associated bacteria can show up early in bathroom biofilms. In kitchens, organisms that tolerate grease and fluctuating pH often do well. Fungi and yeasts can be present too, especially where moisture lingers and there’s a steady trickle of organic material.

The community is not fixed. If a drain sits unused, water in the trap can stagnate and oxygen can drop. If the sink is used constantly, the surface gets shear stress from flow. Both conditions shape the biofilm’s thickness and who persists. Even within one home, the shower drain and the bathroom sink drain can diverge because hair, shampoo polymers, and different drying cycles change the available niches.

Cleaning meets the matrix, not the microbe

Drain biofilms reveal a basic microbial fact: the hardest part to remove is often the environment the microbes built, not the microbes themselves. The matrix slows down chemical penetration and can bind or neutralize some disinfectants. It also creates sheltered pockets where organisms experience less exposure than the surface layer does. So a brief contact can reduce surface cells while leaving a living scaffold underneath that can be recolonized by what flows in next.

Mechanical disruption matters because it changes the structure. When a biofilm is disturbed, pieces can break off. Those fragments can carry a ready-made community downstream, rather than single free-floating cells. That’s one reason a drain can look improved after an intervention and then seem to “come back” quickly: the ecosystem didn’t restart from zero. It restarted from leftovers embedded in seams, scratches, and gasket edges.

A tiny ecosystem with real-world consequences

Most household drain microbes are not a headline hazard, but drains do illustrate how microbes share space and genes. Biofilms are environments where cells are close together, which can make gene exchange easier than in open water. That includes genes for tolerating stresses like detergents or low nutrients. The drain is also a meeting point between household organisms and microbes from the broader water system, so it becomes a small mixing zone for different lineages.

They also highlight how smell works. Odors often come from microbial metabolism in low-oxygen pockets, where sulfur-containing compounds and fatty acid breakdown products can accumulate. That’s why smell can be strongest when water has been sitting and then gets disturbed, releasing trapped gases from the film and the trap. The interesting part is how localized it all is: a few centimeters of wet surface can act differently from the rest of the pipe, just because the biofilm changed the chemistry right there.