A tiny moment with a big reaction

You’re walking down a grocery aisle and a stranger glances up at the exact same time you do. It lasts maybe half a second. Sometimes it feels oddly electric. Sometimes it feels like a warning. This isn’t one single “place” thing, either. It shows up on a New York subway, in a Tokyo elevator, or at a bus stop in London. The quick jolt comes from how the brain treats eyes. Eye contact is a direct signal of attention, intention, and possible action. Even when it’s brief, it can flip the body from neutral to alert before you’ve made sense of who the person is.

Eyes are treated like information, not just a feature

Faces have special priority in perception, and eyes sit at the center of it. People can pick up gaze direction extremely fast, even with limited detail. That speed matters because gaze is about motives. “They saw me” is not the same as “they’re near me.” A glance can imply interest, evaluation, challenge, or help, depending on context. The brain doesn’t wait to be sure. It starts preparing for social consequences right away.

A detail people often overlook is how much of this comes from the white of the eye. Humans have unusually visible sclera compared with other primates, so tiny shifts in gaze are readable. That makes brief contact more “loud” than it seems. It’s not just that someone looked. It’s that you could tell they looked, and they could tell that you could tell.

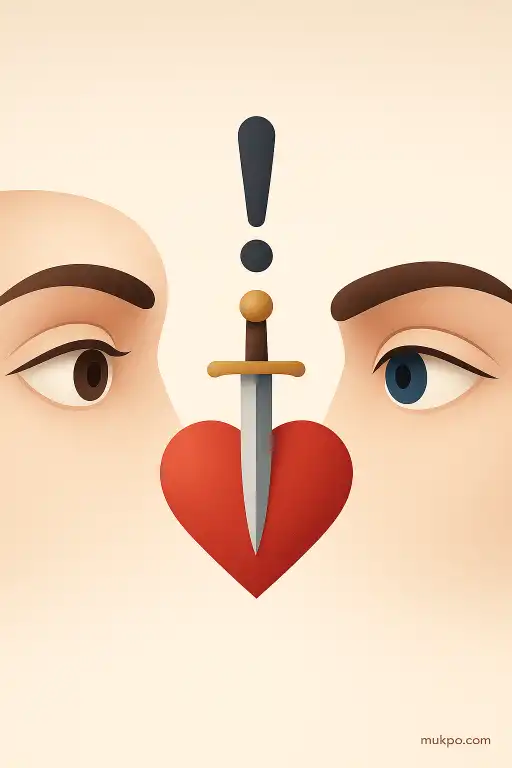

Threat and attraction use some of the same wiring

The body’s arousal systems don’t label their output as good or bad. They raise intensity first. Heart rate changes, attention narrows, and the mind starts sampling for extra cues. That’s why the same half-second can feel thrilling in one setting and threatening in another. A quick look from a person you find appealing at a party can feel like permission. The same look from an agitated stranger in a quiet parking garage can feel like targeting.

There’s also a “mutuality” effect. A one-way stare is different from a shared moment. Mutual eye contact signals that both people are aware of each other at the same time. That can amplify everything. Warmth can feel warmer. Hostility can feel sharper. Ambiguity can feel tense, because the brain now expects a next move.

Culture and setting change what eye contact means

Rules for gaze vary. In some places and situations, direct eye contact is treated as confidence and honesty. In others, it can read as disrespect, flirting, or a challenge. Even within the same country, the “right” amount can shift between a job interview, a bar, a classroom, and public transit. So the feeling isn’t just biology. It’s learned expectation colliding with a reflexive body response.

Setting does quiet work here. Bright lighting, distance, and crowd density all change how interpretable the look feels. In a packed train car, accidental eye contact is common and often ignored, because everyone expects it. In an empty hallway, the same glance carries more meaning because there are fewer competing explanations. The mind treats rarity as significance.

Why a split second can feel like a “moment”

Time perception shifts under arousal. When attention spikes, the brain records more detail. Later, that can make the interaction feel longer than it was. People also fill in missing information fast. A brief look doesn’t provide much data, so the mind leans on stereotypes, past experiences, and current mood to interpret it. That interpretation can arrive as a feeling before it arrives as a thought.

And there’s the simple social fact that eyes are a doorway to identity. Clothes can be generic. Posture can be unclear. A face, even seen quickly, can feel personal. So when two people’s gaze meets, it can feel like an interaction even if nobody speaks, nobody smiles, and nothing else happens.