People often hear “coral bleaching” and picture a reef suddenly turning white, like someone flipped a switch. It isn’t one single event in one place. It’s a stress response that shows up in lots of regions, including the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the Florida Keys in the US, and reefs across the Caribbean. The basic mechanism is surprisingly blunt: when the water stays too warm, coral polyps lose the algae living inside their tissues. Those algae help feed the coral and give it much of its color. Heat pushes that partnership into a bad chemical state, and the coral ends up expelling the algae or losing them.

Coral and algae are roommates, not decorations

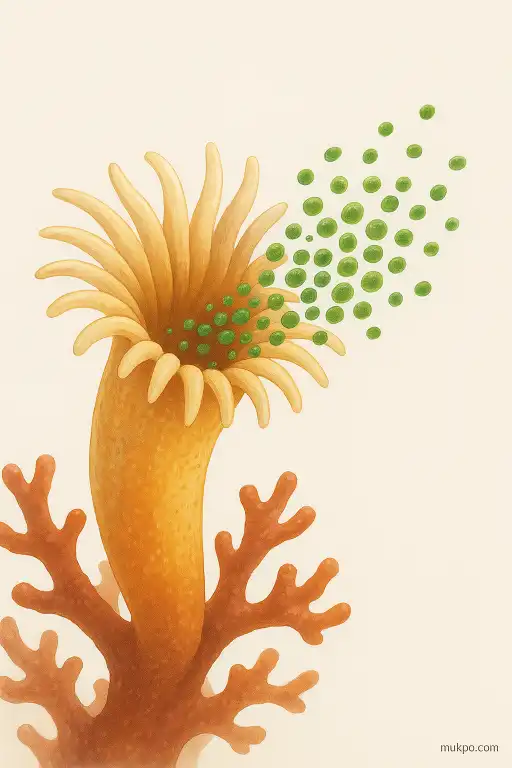

A coral polyp is an animal. It has a mouth, it can capture food, and it builds the hard skeleton that makes a reef. The algae it hosts—often called zooxanthellae, mostly from the family Symbiodiniaceae—live inside coral cells, not on the surface. They photosynthesize and pass a large share of the sugars and other compounds to the coral. That transfer is a big part of why reef-building corals can grow fast enough to create large structures in clear, nutrient-poor tropical water.

The trade is tight and specific. Different coral species tend to partner with particular algal types, and those pairings vary by place and conditions. That matters because “algae” isn’t a single thing here. Some symbionts tolerate heat better than others, and some are better at fueling growth under cooler, stable temperatures. The same coral can sometimes shuffle which symbionts dominate, but it’s limited and not guaranteed.

Warming breaks photosynthesis first

When seawater gets hotter than the coral’s usual seasonal range, the algae’s photosynthetic machinery becomes unstable. The weak link is often photosystem II, where light energy is converted into chemical energy. Under heat stress, that system gets “backed up,” especially under strong sunlight, and more reactive oxygen species build up. These are chemically aggressive molecules that can damage proteins, membranes, and DNA.

One overlooked detail is that heat alone is not the whole experience for the polyp. Bright midday light can turn a marginal temperature into a crisis because it increases the load on photosynthesis at the exact time it’s least stable. That’s why bleaching can be patchy even on the same reef. Corals shaded by structure or depth sometimes hold on longer, while colonies a few meters away in full sun bleach earlier.

Expelling algae is a way to limit collateral damage

Once reactive oxygen species rise inside the coral’s cells, the problem stops being “an algae issue” and becomes an animal tissue issue. Corals respond with antioxidant defenses, stress proteins, and immune-like signaling. If the oxidative stress keeps climbing, the coral may actively eject symbiont cells, digest them, or lose them as host cells detach. Which route dominates varies by coral species and the exact conditions, and it isn’t always clear from the outside what mechanism was most important in a given bleaching event.

From the coral’s perspective, keeping a malfunctioning symbiont can be worse than losing a source of food. Damaged photosynthesis keeps producing harmful byproducts. So the coral “chooses” the option that reduces immediate cellular injury, even though it creates a longer-term energy problem. That tradeoff is why bleaching can look like a self-sabotage but still makes biological sense under acute stress.

What bleaching looks like inside a living colony

The whiteness comes from the coral’s calcium carbonate skeleton showing through more clearly once the algae are gone or greatly reduced. The coral animal is still there at first. You’re seeing thinner, more transparent tissue with fewer pigmented symbionts. Some corals also change their own pigments during stress, which can make bleached colonies look bright pastel instead of plain white for a while.

Losing algae also changes the coral’s daily rhythm. With less photosynthetic input, there is less internally produced oxygen and fewer sugars moving into coral metabolism. That can alter mucus production, calcification rates, and how the coral handles waste products like ammonia. These shifts can start quickly, sometimes before bleaching is obvious from the surface, because the metabolic partnership is already failing even if many symbionts are still present.

Why some corals recover and others don’t

Recovery depends heavily on how long and how far temperatures stay above the local norm. Short heat spikes can lead to partial bleaching and then a rebound if conditions return to typical ranges. Longer marine heatwaves can push corals into starvation, disease susceptibility, and death. Local factors can stack on top of heat stress too, including poor water quality, sediment, and some infections, but the temperature and light stress are usually the initial trigger for mass bleaching.

Even when conditions improve, getting symbionts back is not automatic. Corals may regrow the remaining algae inside their tissues, take up new symbionts from the environment, or shift the mix of types that were already present at low levels. That process takes time and energy, and it can be uneven across a single reef. After a major warm year like 2016 on parts of the Great Barrier Reef, researchers reported stark differences in survival and recovery from one area to the next, even where the corals looked similar from a distance.