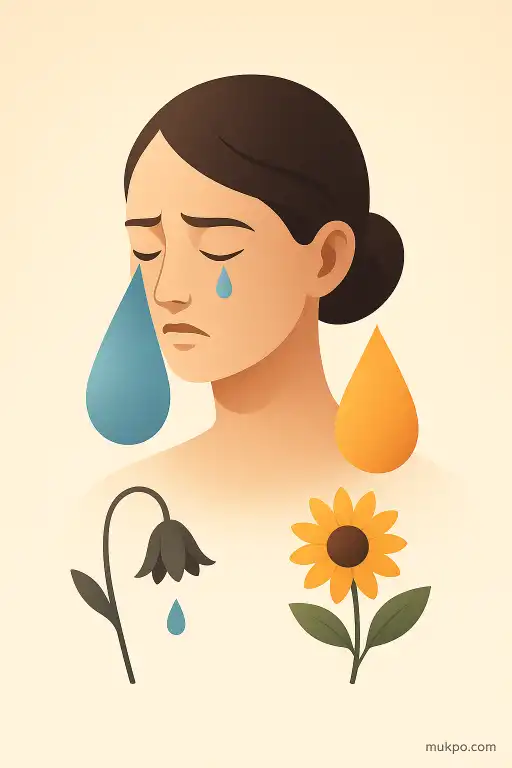

A weird overlap people notice

People notice it at weddings and funerals, and sometimes in the same week. A person can cry watching a couple say vows in a church in Dublin, and cry again at a hospital bedside, and the crying can feel strangely alike in the body. The mechanism is not that joy and grief are secretly the same emotion. It’s that the body tends to use the same high-arousal systems for very different meanings, and tears are one of the simplest ways those systems discharge. The eyes water, the throat tightens, the chest does that stuttering thing. The story in the mind changes, but the plumbing underneath can look similar.

The same tear hardware gets used for different reasons

Humans make different kinds of tears, and emotional crying uses a specific pathway. Signals run through the limbic system and hypothalamus, then down to the brainstem and autonomic nerves that control the lacrimal glands. That pathway doesn’t care whether the trigger was relief, pride, heartbreak, or shock. It cares about intensity. Once the system tips into “too much,” tear production is a common output, like flushing a pressure valve.

One detail people overlook is how much of crying is not “sadness” but reflexive muscle and breathing changes. The throat muscles constrict, swallowing shifts, and the voice box gets unstable. That’s why speech breaks in both happy tears and devastated tears. The body is doing the same coordination problem: breathing, swallowing, and sound production all competing while the autonomic system is revved up.

Joy and grief can both be high arousal

Joy often gets described as light, but it can be physically loud. So can grief. Both can push heart rate up, change skin temperature, and make hands shake. That overlap matters because the body’s arousal dial has fewer settings than the mind’s dictionary. When arousal is high, the nervous system tends to narrow options: faster breathing, more muscle tension, more tearing, less fine control.

That’s also why tears show up with relief. Relief is not calm at first. It’s the moment after sustained tension, when the brain finally allows the body to release it. The feeling can be pleasant and still come with the same wet face and trembling chin that usually gets associated with loss.

Tears can be communication as much as sensation

Emotional crying is a social signal. It’s visible, hard to fake convincingly over time, and it changes how other people behave. Across many cultures, tears can call for closeness, soften conflict, or mark that a moment is important. That social function doesn’t require the emotion to be negative. Happy tears at a graduation or a sports final can broadcast, “This matters,” in a way that words can’t always manage in the moment.

The similarity in “feel” can also come from the face itself. Tears blur vision, the nose runs, the cheeks tense, and the brow changes position. Those facial patterns feed back into the brain through sensory nerves. The person isn’t only expressing an emotion. They’re also receiving strong signals from their own face and breath that something intense is happening, regardless of whether the mind labels it as joy or grief.

Mixed emotions are common, even when people don’t name them

Some events naturally blend happiness and loss. A wedding can carry the quiet grief of time passing, family not present, or a life chapter ending. A funeral can contain warmth, gratitude, and even laughter, and that doesn’t cancel the sadness. When emotions mix, the body can still produce one unified output: arousal plus tears. The person experiences a single surge, even if the meaning is layered.

Sometimes the meaning isn’t even clear while the crying starts. People report crying during reunions, after a long exam, or when an adoption is finalized, and only later decide what the tears “were.” The body reacts first to significance and overload. The mind often catches up afterward, trying to pin a clean label on a moment that didn’t arrive clean.