You can watch this in almost any workshop or practice room. A new drummer sits down, fumbles a basic groove, and then—after a while—the hands start landing in the right places before the person can say what changed. This isn’t one single event or place. It shows up in music rooms in the U.S., driving schools in the U.K., and kitchens everywhere. The core mechanism is that the brain can store “how” in systems that don’t speak in sentences. Those systems learn from repetition, timing, and error. Words arrive later, if they arrive at all.

Two kinds of knowing live in different places

When someone explains a skill, they lean on declarative memory: facts you can state. But a lot of skilled movement sits in procedural memory: patterns you can run without describing. These systems overlap, yet they don’t mature at the same pace. It’s common to see fluent action with weak explanation because the “tell” channel and the “do” channel are partly separate.

That separation is also why a person can recognize the right move when they see it, even if they can’t generate a clean verbal rule. The system that spots timing and trajectory can be strong while the system that turns experience into language lags behind.

Repetition builds a motor program, not a sentence

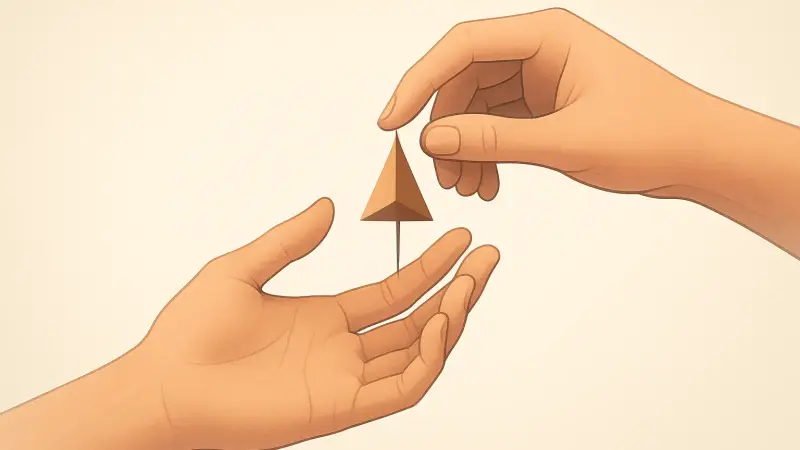

As practice repeats, the nervous system starts compressing action into chunks. Instead of thinking about each finger, it runs a package: this grip, then this pressure, then this release. That chunking is one reason complex skills suddenly feel “automatic.” It’s not that thinking stops. It’s that fewer decisions need to be made moment to moment.

A specific detail people overlook is timing. Not big timing, like “play faster,” but the tiny spacing between elements. In drumming or typing, differences of a few tens of milliseconds can separate “clumsy but correct” from “smooth.” Learners often change those micro-delays without noticing. Later, they may invent a story about posture or confidence because the real change was too small to feel directly.

Your brain learns by prediction and correction

Skilled movement relies on prediction. The brain guesses what will happen if it sends a command, then compares that to what actually happened. The gap is an error signal. Over many cycles, the system reduces the error. This is why performance can improve even when someone can’t name what they’re improving. The learning is driven by mismatch, not by explanation.

That error-correction loop can work without full awareness because it uses fast sensory feedback. Touch, balance, and proprioception update continuously. The adjustments are often too quick for conscious narration. By the time language tries to report, the hand has already corrected course.

Words can trail behind because awareness is limited

People don’t have direct access to most of the computations that stabilize movement. Attention is a narrow spotlight. It tends to track the goal—hit the note, keep the car centered, slice evenly—while the detailed control work happens elsewhere. When asked to explain, a person often reports what they were attending to, not what the motor system was tweaking.

This is one reason confident explanations can be unreliable. Someone might say, “I relaxed my shoulders,” because that was the only noticeable change. But the improvement could have come from a quieter grip force, a slightly earlier brake release, or a different wrist angle—variables that are hard to perceive without measurement.

Explaining can sometimes disrupt the skill you just gained

Once a pattern is procedural, forcing it into step-by-step language can pull it back into conscious control. That shifts timing. It can make movements stiff, slower, or oddly segmented. Sports psychologists sometimes call this “reinvestment,” where attention returns to mechanics that used to run in the background.

You can see it in a concrete moment: a person parallel parks smoothly, then tries to teach it. On the next attempt, they narrate each step and the steering gets late. The skill didn’t disappear. The control system changed because the act of describing recruited different processes than the act of doing.